Saving Syria’s Children: the sequel

BBC Panorama has produced a follow-up report to 2013’s Saving Syria’s Children (SSC).

The new documentary, entitled Syria’s Schools Under Attack (SSUA), is produced, filmed and narrated by SSC director and cameraman, Darren Conway. [1]

SSUA was screened several times over the weekend of 20/21 March 2021 on BBC World News and BBC News Channel. An extended version was broadcast solely on BBC World News on 24 and 25 April. As far as I am aware this is the first time an edition of Panorama, the BBC’s flagship current affairs series, has not been broadcast on BBC1.

The programme includes interviews with several of the alleged victims and relatives from SSC. It contains several inconsistences with the original documentary as well as fresh incongruities which raise new questions.

The observations below are discussed as they arise in SSUA. (BBC iPlayer copy here, YouTube copy here and above). [3]

02:30 – “We heard sound of a warplane like in the air”. (Abu Taim, teacher) [4]. “There were more than 75 children at school that day. Abu Taim started to evacuate his students from the classrooms immediately after the bomb struck the school’s courtyard”. (Conway)

This account suggests [A] that the first intimation of anything unusual that day was the sound of a warplane above the school and [B] that the students only began to leave their classrooms after a bomb hit the school’s courtyard. [5]

In respect of [A], accounts by Dr Saleyha Ahsan, Dr Rola Hallam, another purported teacher at the Iqra school and journalist Paul Adrian Raymond [6] all refer to an initial attack on a nearby apartment building shortly prior to the attack on the school. The first attack was also confirmed by the BBC in correspondence [7].

In a November 2020 Human Rights Watch report victim Muhammed Assi [8] recounts how, after the initial attack on a three-storey building 100 metres away [9], he and other students hurried outside to see what had happened:

““We saw a plane in the sky. It was very far away so we thought, ‘OK, it won’t hit us,’” Muhammed told Human Rights Watch and IHRC. Teachers urged the students to return inside where it was safer. Muhammed and five classmates, however, stayed in the courtyard with a playground talking about the attack and what they would study the following year. The group suddenly heard a faint, “unfamiliar” sound, and “[t]here were large fires, and choking fumes.” An incendiary bomb had landed in the middle of the six students, immediately killing the other five”.

In respect of [B], in the BBC’s initial report of the incident Conway’s colleague Ian Pannell states (00:15):

“What happened here almost defies words. The end of the school day, a playground full of teenagers and an incendiary bomb that killed over 10 pupils and left many more writhing in agony”.

This would seem to contradict Conway’s statement that Abu Taim began to evacuate students only after the bomb had hit the school and Assi’s testimony that just he and five classmates were outside when the bomb struck the playground.

Dr Rola Hallam has also claimed on several occasions that the playground was full of children when the attack occurred, for example:

“a schoolyard full of children was aerially bombarded with an incendiary weapon”. [10]

“a big incendiary weapon which is basically a big ball of fire that was dropped from the aeroplane. Onto a, umm, a school yard where ten to sixteen year-olds were waiting after school to be picked up by their children, by their parents”. [11]

Adding to the contradictions Dr Saleyha Ahsan has claimed that parents and family members had rushed to the school after the initial bombing of the nearby residential building and consequently were also present when the second bomb struck:

“The first bomb had hit a nearby building penetrating three floors and injuring my first patient, the baby. Everyone ran to help. Parents had rushed to the school on the first hit to take their children home. Anas had come for his 14-year-old sister – a student. She was saved but he was so terribly burnt”. [12]

These accounts by Ahsan, Hallam and Conway’s SSC colleague Ian Pannell appear inconsistent with the picture painted in SSUA of students sitting in their classroom oblivious to the possibility of an impending attack. [13][14]

03:40 – “It was a children’s hospital run by a local charity called Hand in Hand for Syria“.

Hand in Hand for Syria was a UK registered charity, not a local Syrian charity. Three of its executive team are now trustees of another UK charity Hand in Hand for Aid and Development.

A June 2014 article on Hand in Hand for Syria’s website makes it clear that Atareb was a general, not a children’s, hospital:

“When we first opened the hospital in May 2013, it was just a small A&E unit. We’ve grown it very successfully since then, and it now offers 68 beds and a wide range of services – from maternity and neo-natal facilities to many outpatient departments, three excellent operating theatres and a laboratory. It cares not only for those injured in the conflict but also non-conflict-related conditions such as cancer, heart disease, asthma and diabetes. It even has a dialysis unit. It provides FREE healthcare to anyone, regardless or political or faith affiliation”. [15][16]

03:46 – 04:00 – This scene features the Hand in Hand for Syria nurse who was later photographed at the same hospital “treating” a child fighter. [17]

The sequence also features the “burnt” father and baby.

04:23 – A girl’s scream is patched into the soundtrack here and again at 05:38. The same disembodied scream was also woven into the soundtrack of SSC at 33:26 and 34:41.

04:25 – An ISIS insignia is visible in the rear window of the ambulance filmed by Conway as it enters Atarab Hospital’s courtyard. As discussed here, the Panorama team was embedded with then ISIS partners Ahrar al-Sham during the production of SSC, enabling them to pass unmolested through an ISIS checkpoint. Were the occupants of the ambulance, at least one of whom was armed, members of ISIS? [18]

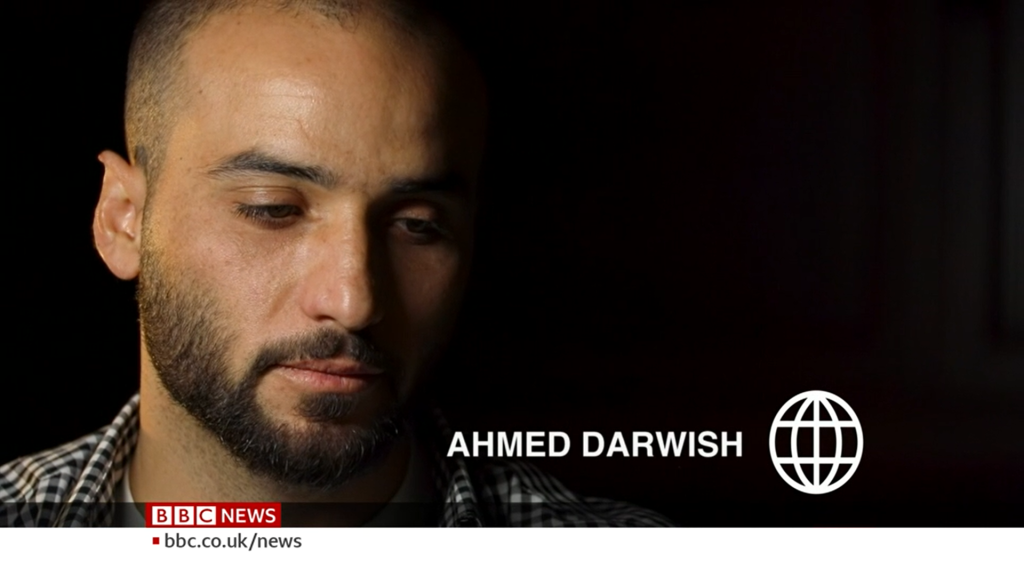

07:55 – “This is Ahmed Darwish, he was 16 years old”.

Here is the person named as Ahmed Darwish as he appears in SSUA:

Here he displays scars:

The person referred to as Ahmed Darwish in SSUA claims to be the person in the striped top who was shown in SSC being carried into Atareb Hospital on 26/8/2013:

The young man in the striped top was not named in SSC.

However it is striking that in SSC a younger child was named as Ahmed Darwish – the small boy shaking in a chair in the corridor:

If there were only one person named Ahmed Darwish involved in the events of 26/8/2013 and the misattribution of the name by the BBC, either now or in 2013, were simply an error, it would be an odd one to make. The “original” Ahmed Darwish was one of the focal points of SSC, appearing in the Atareb Hospital sequences and towards the end of the programme, where he is seen in a different hospital recovering from his alleged injuries. [19]. In 2014 SSC reporter Ian Pannell claimedhe and Conway had “sporadic contact” with Ahmed’s father. Panorama used an image of the “original” Ahmed Darwish in its promotion for SSUA in April 2021.

As discussed in this recent post, the Violations Documentation Centre in Syria (VDCS) compiled a list of 41 fatalities of the alleged attack. [20] The list contains several names plainly recognisable from SSC, albeit transliterated slightly differently in some cases (for instance the BBC refers to one of the victims as Lutfi Arsi while the VDCS lists a Loutfee Asee). The VDCS list contains a single victim named “Ahmad Darwish“.

A peculiar point about the VDCS list is that it gives the date of death of all those on it as 26/8/2013, the day of the alleged attack. However some of those listed are claimed by the BBC to have either died some time later (e.g. Anas Sayyed Ali, listed by the VDCS as Anas al-Sayed Ali) or to still be alive (e.g. Muhammed Assi, listed by the VDCS as Muhammad Assi).

In 2014 Ian Pannell stated that the “original” Ahmed Darwish – the small boy shaking in the corridor – “is alive and living back in Syria”. Evidently the “new” Ahmed Darwish – the balding, bearded man seen in SSUA – survived the events of 26/8/2013.

10:09 – “This is Ahmed’s classmate Omar Misto. He also managed to escape Syria and lives in Turkey now”.

Omar Misto had not previously been named by the BBC.

At 11:23 in the extended version of SSUA Omar Misto describes the events of 26 August 2013:

“After we were attacked, I saw a bright light so I closed my eyes and hugged myself. I laid on the ground, because of the high temperature I didn’t feel the burn. I just felt warmth, and I knew something had happened. In that moment I thought I’m dying. After that I think… I blacked out for a few seconds. When I woke up, I saw flames on my back, and my hands. My left leg was burning and without a shoe.”

One might question how one could see flames on one’s back.

If in stating that his “left leg was burning” Omar Misto meant that his left leg was alight, this would seem to be belied by the shots in SSC of the teenager in the aftermath of the alleged attack which show his jeans somewhat torn but unburnt.

As in the case of Ahmed Darwish above, and other alleged victims presented in SSC and SSUA, an anomaly exists between the BBC’s accounts and the casualty list compiled by the VDCS. According to the VDCS two children, Omar Mestow and Muhammad Mestow were among those who died in the attack on 26/8/2013. Bearing in mind the very close correlation between other names ascribed to victims by the BBC and names on the VDCS list, plus the fact that according to SSUA Omar’s brother was named Mohammed (see below), it is safe to assume that the names Omar Misto and Omar Mestow refer to one individual. However, clearly – according to SSUA – Omar did not die on the day of the attack and, as we shall see below, neither did his brother Mohammed.

10:52 – “he [Omar] has had 25 operations“.

How did a student from a rural Aleppo town pay for 25 operations? Where and when did they take place? If his treatment involved leaving and returning to Urm al-Kubra, how was he able to move in and out of territory controlled by jihadist groups? [21]

11:20 – “And this is his younger brother Mohammed. He’s 15”.

Mohammed Misto had also not previously been named by the BBC.

Mohammed Misto features in the “tableau” scene in SSC and associated BBC News reports. He is the boy in the black vest on the right of the image below. Following a gesture by Muhammed Assi (the central figure in the tattered white t-shirt) Mohammed Misto rolls over onto his right then sits back up, glances in the direction of the camera and peers around the room. In the full sequence he then slumps onto his front. The “tableau” sequence is included in SSUA at 05:47 and there are a few seconds of previously unbroadcast footage from it at 13:28.

12:18 – “Mohammed Misto died eight days later“.

As noted above, a Muhammad Mestow is listed by the VDCS as having perished in the same “Warplane shelling” as Omar Mestow and other familiar names from SSC (and now SSUA) on the date of the alleged attack, 26/8/2013.

More perplexingly still, a casualty reportpublished by the Damascus Center for Human Rights Studies (DCHRS) on 25 November 2013 lists “6 victims who have fallen in previous days”. The report states that the victims were “killed by indiscriminate shelling of the Syrian regime warplanes” in “Orm Al-Kubra” on 28/6/2013, two months before the alleged airstrike of 26/8/2013 featured in SSC. The list includes the name “Mohammad Mastou”.

As discussed here, two other names on the above list – Seham Qanbri and Lutfi Assi – have close parallels with victims named in SSC. Five of the six have close parallels with names on the VDCS casualty list of 26/8/2013.

How is it possible for the same victims to have apparently died on 28 June 2013, again on 26 August 2013 and then, according to the BBC, for some of them to have died at an even later date?

| DCHRS casualty report – date of death in all cases 28/6/2013 | VDCS casualty report – date of death in all cases 26/8/2013 | BBC sources |

| Seham Qanbri | Siham Qandaree – child female | Siham Kanbari – died 19/10/2013 (end credits of SSC). |

| Lutfi Assi | Loutfee Asee – child male | Lutfi Arsi – “died on his way to hospital”, i.e. either 26/8/2013 or 27/8/2013 (BBC Complaints) |

| Mohammad Mastou | Muhammad Mestow – child male | “Mohammed Misto died eight days later”, i.e. 3/9/2013 (SSUA) |

| Walaa Aqraa | Walaa al-Ali – child female | not named in BBC’s reports |

| Wesam Hussein | Wisam Hosain – adult male | not named in BBC’s reports |

| Mustafa Ash-Shaikh | Mostafa al-Shaikh – adult male | not named in BBC’s reports |

Is part of the explanation that the DCHRS simply made a mistake, erroneously recording 26/8/2013 as 28/6/2013? I have contactedthem to request clarification but have not received a response.

12:34 – The groaning from the “tableau” sequence is patched into the soundtrack here.

12:38 – “This is Muhammed Assi. He suffered 85% burns to his body”.

Muhammed Assi is the central figure in the “tableau” scene in SSC and related BBC News reports. He looks directly into the camera for several moments before raising his arm, at which point the rest of the group becomes animated:

This video, filmed in Urm al-Kubra in 2018, appears to corroborate that Assi has at some point sustained injuries:

Further observations on Assi’s injuries are noted towards the end of footnote [22].

At 04:22 in the BBC1 News report of 16 March 2021 Conway narrates:

“For 23 year old Muhammed the future is not bright”.

Both the BBC in complaints correspondenceand Human Rights Watch in its November 2020 report have stated that Assi was 18 at the time of the attack in August 2013. The Human Rights Watch report further states that Muhammed is “now 25 years old”.

12:45 – “This is me after arriving. I was in a red pickup vehicle”. (Muhammed Assi)

This detail is also mentioned by Omar Misto at 11:27:

The red pickup truck is also mentioned by Darren Conway in an interview (from 01:54:10) on the BBC Radio 4 Today programme on 17/03/2021. [22]

“There are a couple of students that, er, really stayed in my mind, one I guess is Muhammed Assi, he had this white powder all over his face, he had burns all over his face, all over his body in fact. As it turns out, we now know that that Muhammad Assi had burns to 85% of his body, that’s 85% of his body and he arrives on a (pause) red pickup truck and he walks himself into a hospital, I mean it it was not only shocking but it was heart-breaking”.

The inclusion of this insignificant detail by three individuals in linked BBC reports appears unnatural and coached.

13:51 – “They were my friends since the first grade“. (Muhammed Assi)

Assi’s statement gives the impression that the Iqra school in Urm al-Kubra was a regular Syrian state school which the students had all attended together for some years. However BBC Complaints Director Colin Tregear has said (p10):

“My understanding is that the vast majority of schools in Syria have shut down as a result of the ongoing conflict within the country. Many students have not been to school for many, many months. Some private schools have been set up and these are often run from any available premises. In this case I have been informed that the venue was a residential home hired by the headmaster and his colleagues, and they were holding summer courses at the time of the attack”.

In the extended edition of SSUA (35:35) Abu Taim states “At that school I had been working three years”.

The Syrian conflict began in March 2011. If the Iqra school were, as the BBC Complaints Director understands, a private establishment set up in response to the conflict, it would not have existed three years prior to August 2013.

Moreover, as discussed towards the end of this piece, the school’s name “Iqra” may indicate that it was a religious institution established by one or other of the jihadist groups holding the area and to which parents sent their children primarily in order to demonstrate loyalty. If so, this raises questions about the mix of male and female students and the casual attire of the teaching staff as presented in the BBC’s reports.

16:50 – “17 year old Siham was in her maths class at Iqra school when the blast ripped through the window”.

The BBC and Human Rights Watch have previously given Siham’s age at the time of her death as 18. Saleyha Ahsan has described her as a “young 16 year old girl”.

If Siham were between 16 and 18 in 2013, had she survived then in 2020, when SSUA was filmed, she would have been between 22 and 25. There would therefore appear to be a very large age gap between her and her younger brothers as depicted in SSUA.

In a March 2021 article Dr Rola Hallam names Siham’s father as Abu Mahmoud and quotes him as follows:

“I am terrified each time I send my twins to school, will I see them as I saw Siham, their skin melting in front of my eyes?”

However the two boys filmed with their alleged father in SSUA are self evidently different heights and different ages.

17:53 – This shot of Siham Kanbari is captioned “Ankara Children’s Hospital 19 September 2013”. Part of the same footage also appears in SSC from 43:22.

However in complaints correspondence with the BBC in 2014 Ian Pannell stated that the footage of Siham was shot at the Diskapi Yildirim Beyazit Training and Research Hospital in Antakya.

“The IEA asked about the circumstances surrounding the follow-up visit to the hospital in Turkey a few weeks later, sequences from which were shown in the subsequent Panorama. Both men went to Turkey and the IEA was supplied with the name of the doctor who treated the victims and who could attest to their injuries and the facts of Siham Qanbari’s death. Ian Pannell said:

“The hospital was the Diskapi Yildirim Beyazit Training and Research Hospital in Antakya – home to one of the country’s specialist burns units. It may be worth adding here that we spent two days in meetings trying to secure permission to film inside the unit as the Turkish government has a policy of refusing media access. It was an eleventh hour decision by the head of the burns unit to approve our request just four hours before we were due to board a plane back to Istanbul.

“We arranged the visit ourselves. (Our fixer) had been in contact with the head of the burns unit and the BBC’s Istanbul Producer was in contact with Turkish health officials.””

Update: I have been informed that the Diskapi Yildirim Beyazit Training and Research Hospital is in Ankara, not Antakya. Presumably therefore this was simply an error on the BBC’s part. However the same source advises that there is no hospital named Ankara Children’s Hospital.

Regarding the date in the caption, 19 September 2013, a discrepancy arises. Footage of alleged victim Ahmed Darwish in hospital is presented alongside that of Siham in SSC (from 43m). The furnishings of Siham’s and Ahmed’s rooms are very similar, suggesting that they were both filmed at the same facility. However, as discussed at footnote [19] below, Ian Pannell has previously indicated that the footage of Ahmed Darwish was filmed “about a week” after the alleged attack, i.e. around 2 September 2013. There is no suggestion that the Panorama team made more than one follow up visit to the Turkish hospital.

18:50 – “Siham died one month after begging the world to stop the suffering in Syria”.

As discussed above and here a Seham Qanbri and other familiar names from SSC are listedby the DCHRS as victims of a warplane shelling in Orm Al-Kubra on 28/06/2013, two months prior to the alleged events reported by the BBC.

According to VDCS a Siham Qandaree, age 17, and an adult, Siham Qonbori, “fell due to Syrian Regime airstrike using Napalm” on 26/8/2013, the date of the alleged attack.

The DCHRS also reports that a Siham Qambri from Aleppo was “killed by indiscriminate shelling of the Syrian regime warplanes” in Orm Al-Kubra on 23/10/2013.

In a blog post dated 21st November 2020, Dr Rola Hallam states:

“I found out only last month [i.e. October 2020] that Siham had passed on, unable to survive the devastating burns that had ravaged her body.”

This statement is implausible.

Writing for the Daily Beast in December 2013, Paul Adrian Raymond asserted that Siham died seven weeks after the attack, i.e. approximately 14 October 2013.

At some point prior to September 2014 (when SSC was removed from BBC iPlayer), the BBC updated the programme’s end credits, stating that Siham died “On October 19th [2013], 8 weeks after the attack”.

Furthermore, Dr Hallam’s colleague on SSC, Dr Ahsan, stated in a blog post of her own of 25th November 2013:

“On Oct 20, nearly two months after she was injured, Siham died.“

Given these contemporary announcements by a widely read online news outlet, the BBC itself and Dr Hallam’s colleague and friend Dr Ahsan, how is it feasible that Dr Hallam had only learned about Siham’s alleged death a full seven years later, in October 2020?

19:57 – “This is Bayan Khannas, with her brother Muhammed”.

At 02:55 in the accompanying BBC News website report of 17 March 2021, Syria: The scars left by a school bombing, Bayan says of her brother:

“The palms of his hands were burnt and there were holes in his shirt. His hair was burnt”.

This is a peculiarly understated account of Muhammed’s alleged injuries. As is plain from sequences in SSC and repeated in SSUA, Muhammed arrives at Atareb Hospital, accompanied by Bayan, with his skin apparently falling off his hands and arms and with his shoulders and back apparently severely burned. Bayan is shown applying cream to her brother’s burned back and shoulders.

Note that the VDCS fatality list for the alleged attack includes a female child victim Bayn Khansa.

21:06 – “Mohammed died two days after the attack on his school. He was 15 years old”.

This conflicts with information presented in SSC (42:26):

“Muhammed Khannas, 14 years old. He died on the way to hospital in Turkey”.

This would indicate that Muhammed died either on the day of the attack or early the next morning, i.e. 26/8/2013 or 27/8/2013.

While Mohammed Khanass does not appear on the VDCS fatality list, a “Mohamad Feda Khenass” is appended to a truncated version of the VDCS list which is included in a November 2013 Human Rights Watch report (p20). This may indicate that Mohammed died after 26/8/2013, the date of death ascribed to all those on the original VDCS list.

The DCHRS lists a “Child Mohammad Fida Khannas” as a fatality from a warplane shelling on Orm Al-Kubra on 30 August 2013.

Notes

[1] Ian Pannell, the reporter on SSC, subsequently left the BBC to work for American broadcaster ABC. In 2019 Pannell narrated a report which misrepresented footage from a Kentucky firing range as a Turkish assault on Kurdish civilians in a Syrian border town.

[3] Reference is also made to the following related BBC News reports:

- Ten years of terrible suffering as Syria’s civil war grinds on, BBC1 News, 16 March 2021

- Syria: The scars left by a school bombing, BBC News website, 17 March 2021

- Interview with Darren Conway, Today, Radio 4 (from 01:51:40), 17 March 2021

- Syria’s Schools Under Attack (extended version), BBC World News, 24/25 April 2021 (off screen recording)

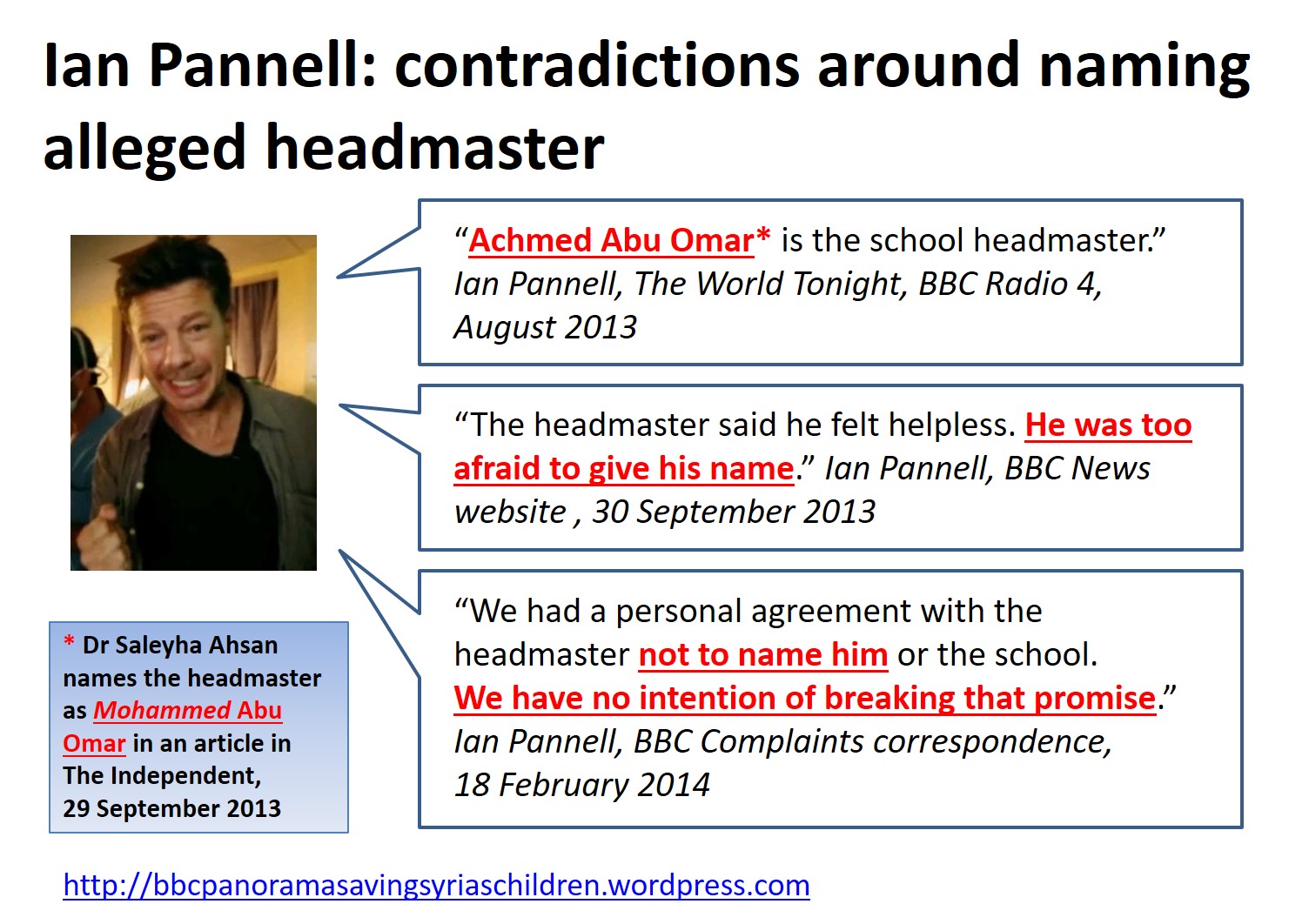

[4] It is unclear to me whether “Abu Taim” is the same teacher who speaks in this November 2020 Human Rights Watch video(at 3 mins 11s) and who is described as Iqra school’s headmaster in SSC (from 41 mins 40s). If so, then SSC reporter Ian Pannell and Dr Saleyha Ahsan have previously named him, possibly pseudonymously, as Achmed Abu Omar and Mohammed Abu Omar respectively.

[5] This scenario is echoed by Ian Pannell in the narration of SSC (37:09) where he states that “eighteen year old Siham had been sat in a maths class when the blast ripped through the window”.

[6] Collated in Section 13 (Number of bombs), Second letter of complaint to BBC | Fabrication in BBC Panorama ‘Saving Syria’s Children’ (wordpress.com)

[7] Section 13, BBC response to second letter of complaint | Fabrication in BBC Panorama ‘Saving Syria’s Children’ (wordpress.com):

“There were two attacks. There is eyewitness footage from the first that we have seen: it was a residential apartment block. The second attack was on the school”.

Two separate attacks are also indicated in these remarks by alleged victim Ahmed Darwish:

[8] Both Human Rights Watch and SSUA transliterate the name this way. I will use this spelling here when not citing other sources.

[9] This analysis indicates that the apartment building was in fact on the next block along from Iqra school, considerably closer than 100 metres away.

[12] Ian Pannell’s claim in SSC (42:32) that alleged victim Anas Said Ali had “been waiting to pick up his little sister from school” suggests a normal school day routine rather than Dr Ahsan’s hectic scenario of parents and relatives rushing to the school following a bomb.

Dr Hallam’s claim in [11] that “ten to sixteen year-olds were waiting after school to be picked up by their… …parents”, also indicates a normal day but here it is the children who were waiting for their parents and/or family members rather than vice versa.

[13] At 35:45 in the extended version of SSUAwe hear more of Abu Taim’s account:

“We heard sound of a warplane like in the air. But we didn’t imagine that this criminal pilot will attack like civilians, will attack innocent students. The explosion was horrible and and we saw like a kind of smoke and the smell were like was terrible and we started to evacuate the students to a safe place so we thought everyone like was safe until we went to the front of the school where the playground and then I saw, I saw bodies of my students”.

If there had indeed been an initial strike just a short time earlier on a residential building 100 metres away – according to Human Rights Watch – or indeed on the very next block – see note [9] – then Abu Taim’s faith that a pilot would not attack civilians is inexplicable.

[14] This purported teacher from the school claims that the students started to be evacuated after the first alleged bomb attack on the nearby residential building, prior to the school being struck:

“The plane hit a residential area in Urum Al-Kubra … we tried to get out quickly so we didn’t get hurt but it seems someone’s fate caught up with them today. A gathering of students formed which is normal as the students needed to leave under these circumstances and the plane hit us”.

[15] The dialysis machine and an adult patient were featured on Atareb Hospital’s Facebook page a month prior to the filming of SSC.

[16] More details of the clinics that were available at Atareb Hospital at that time are detailed on the website of the NGO Orient for Human Relief, which partnered with Hand in Hand for Syria to fund Atareb Hospital between April and August 2013. Orient for Human Relief was founded by Dubai based Syrian entrepreneur Ghassan Aboud. Further details of Atareb Hospital’s funding history can be found here.

[17] Hand in Hand for Syria employee Iessa Obied has posted social media images of himself posing with an arsenal of weaponry. The Charity Commission found that these images and other information about Obied’s associations “do not raise sufficient regulatory concern”.

Iessa Obied is the younger brother of Atareb Hospital’s then Medical Director, Abdulrahman Obied. Abdulrahman is filmed in conversation with Dr Hallam at 07:34 in SSC.

2nd row: Dr Hallam and Abdulrahman Obied in SSC; Iessa Obied posing with surface to air rocket launcher.

3rd row: the Obied brothers and their father.

4th row: Iessa Obied with more weapons and armaments.

[18] The ambulance was transporting a female alleged victim. As discussed here, this woman was able to walk unaided into the ambulance at the outset of her journey yet was filmed by Conway at Atareb a short time later being carried out of the same vehicle by five men, two of whom had accompanied her into the vehicle and so were fully aware that she could walk.

[19] Precisely when the latter sequence was filmed is unclear. In September 2013 Pannell wrote “We visited Ahmed, in a Turkish hospital, a few weeks after the incident.” However a Word document authored by Pannell in February 2014 (part of my complaints correspondence with the BBC) states “here is a screen grab of Ahmed about a week later in hospital in Turkey”. The image appears to be from the sequence shot by Conway:

[20] VDCS appears to have removed this list sometime after I published this analysis in January 2021. I have included a link to a copystored on the Wayback Machine. The individual listings for victims linked to from the main list are still accessible on the VDCS site.

[21] Similar questions apply in respect of Muhammed Assi. Human Rights Watch reportsthat Assi “has since received psychological treatment from a Syrian doctor in France”. The same Human Rights Watch report states:

“He took jobs as an aid worker with a Syrian nongovernmental organization that provides heaters for refugees in camps before winter and as a security guard protecting equipment at a Covid-19 isolation center”.

At 18:44 in the extended edition of SSUA Conway states:

“Muhammed roams the streets during the day looking for work”.

With presumably very modest resources, how was Assi able to fund his travel to France for psychological treatment?

As evidenced by the video Assi was resident in Urm al-Kubra in March 2018. We learn from SSUA (12:59) that he now “lives in Idlib, rebel held north west Syria”. How was Assi able to move freely in and out of “rebel” held areas?

[22] Conway’s interview, which commences at 01:51:40, raises a number of further questions.

01:52:12 – “We were filming inside the hospital and a baby had just come in and Dr Rola [Hallam] and Dr Sal [Saleyha Ahsan] were treating that baby. I heard a commotion outside, I remember it vividly because it was a pretty quiet day and the hospital was fairly empty except for the baby who was crying and then I heard this commotion outside. I sort of decided to go out and have a look”.

Drs Hallam and Ahsan have provided differing accounts of the start of the crisis. Dr Ahsan, while concurring with Conway that “it was quite a quiet day”, has claimed that the first victim she encountered was not a baby but rather a boy with “wide staring eyes” who asked her where he should go. In another account Dr Ahsan stated that an ambulance siren preceded the simultaneous arrival of the baby and young girls:

“The sound of an ambulance siren and then the screams first of all from a baby and then young girls – that I still hear as I write this – alerted me that something disastrous had happened”.

More starkly at odds with all previous tellings of the alleged incident, in 2017 Dr Hallam claimed that, far from the “quiet day” described by Conway and Ahsan, the staff of the hospital were sheltering in the hospital basement because a warplane was flying overhead.

In the same account Dr Hallam also omits any reference to a baby, instead claiming:

“So we’d just come out [of the basement], and one by one we were seeing these ghoulish-looking children walking in”.

01:53:02 – The groaning from the “tableau” sequence is patched into the soundtrack here, again at 01:53:49 and at the conclusion of the report at 01:56:48.

01:53:25 – “I also noticed some kind of white, sort of powder stuff on them, we didn’t know what this white powder would have been, this had obviously come from the incendiary weapon that was used and it wasn’t only on the outside of their bodies but they’d breathed it in as well, and that’s ultimately what was causing them burning inside the body as well as out.”

Conway’s belief that the white powder “had obviously come from the incendiary weapon” is peculiar as the narrative has long been established that the munition used in the alleged attack contained an incendiary gel. In September 2013, less than a month after the alleged incident, Dr Ahsan wrote on the BMJ website:

“Peter Bouckaert, of Human Rights Watch, believes the weapon was a ZAB incendiary device. It contains a jellied fuel which “adheres to the skin increasing the level of injury … it’s a nasty weapon””.

Moreover the source of the white powder was explained in Human Rights Watch’s November 2020 report:

“At first, the medical staff did not know the source of these patients’ severe burns and the white powder that covered them… …They were later told that the white powder covering the victims was actually dust from the impact of an incendiary weapon”.

01:55:38 – “He [Assi] has pain almost every day and discomfort”.

Human Rights Watch states of Assi

“Although he no longer feels chronic pain, scars cover 85 percent of his body and he can no longer use his left hand”.

Regarding HRW’s claim that Assi “can no longer use his left hand” note the sequence in the BBC News website report of 17 March from 06:16 in which Assi removes his shirt with both hands and sweeps his hair over his head with his left hand with no apparent impediment.

Note too the below images from Assi’s Instagram account from between 2018 and 2021 in which he appears to favour his left hand when taking selfies and holding his phone.

No comments:

Post a Comment