The US is building a bioweapons lab in Kazakhstan

When it opens in September 2015, the laboratory in Almaty will serve as a way station for a global war on disease

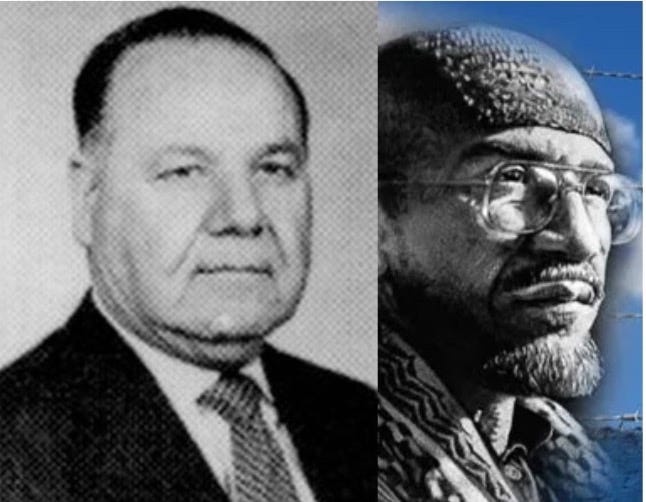

In 1992, Dr. Kanatjan Alibekov, a biologist from the Soviet Union, boarded a flight in Almaty, then Kazakhstan’s capital, for New York. When Dr. Alibekov—now known as Ken Alibek—sat down with the CIA, he had a terrifying secret to reveal: that bio weapons program the Soviet Union stopped in the 1980’s hadn’t actually stopped at all. He knew this because he had led Moscow’s efforts to develop weapons-grade anthrax. In fact, he said, by 1989—around the time that Western leaders were urging the USSR to halt its secret bioweapons program, known as Biopreparat—the Soviet program had dwarfed the US’s by many orders of magnitude. (This is disregarding the possibility that the US was also developing some of these weapons in secret, and, like Russia, still is.)

One big problem, he added, was that, like the stockpiles of nuclear weapons left in the dust of the Soviet Union, the materials and the expertise needed to make a bioweapon—anthrax, smallpox, cholera, plague, hemorrhagic fevers, and so on—could still be lying about, for sale to the highest bidder. Of those scientists, Alibek told the Times in 1998, ”We have lost control of them.”

Today, biologists who worked in the former Soviet Union—like those who responded to a case of the plague across the border in Kyrgyzstan this week—are likely to brush Alibek’s fears aside. But they’ll also tell you that the fall of the Soviet Union devastated their profession, leaving some once prominent scientists in places like Almaty scrambling for new work. That sense of desperation, underlined by Alibek’s defection to the US, has helped pump hundreds of millions of dollars into a Pentagon program to secure not just nuclear materials but chemical and biological ones, in a process by which Washington became, in essence, their highest bidder.

This explains the hulking concrete structure I recently visited at a construction site on the outskirts of Almaty. Set behind trees and concrete and barbed-wire, Kazakhstan’s new Central Reference Laboratory will partly replace the aging buildings nearby where the USSR kept some of its finest potential bioweapons—and where scientists study those powerful pathogens today. When it opens in September 2015, the $102-million project laboratory is meant to serve as a Central Asian way station for a global war on dangerous disease. And as a project under that Pentagon program, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, the lab will be built, and some of its early operation funded, by American taxpayers.

The far-flung biological threat reduction lab may look like a strange idea at a time of various sequester outbreaks, but officials say it’s an important anti-terror investment, a much-needed upgrade to a facility that has been described as an aging, un-secure relic of the 1950’s, and one that the Defense Dept. fears can’t keep pace in an era of WMD.

It’s also an investment, they add, in a country where scientists are hungry for more international participation and better facilities—and where the U.S. is keen to keep sensitive materials and knowledge in the right hands and brains.

“You cannot erase this knowledge from someone’s mind,” said Lt. Col. Charles Carlton, director of the US Defense Threat Reduction Agency office in Kazakhstan. The threat of scientists going rogue, he said, is “a serious concern.” “We’re doing our best to employ these people. Our hope is that through gainful employment they won’t be drawn down other avenues.”

There is no hard evidence that bioweapons were pilfered and sold during the 1990s, but Alibek has said that “there are many non-official stocks of smallpox virus,” a virus that was officially eradicated in 1980. Western intelligence agencies also estimate that North Korea and Russia currently have the capacity to deploy smallpox as a weapon of mass destruction. (It’s worth remembering however that fears in the run-up to the Iraq war about Saddam Hussein getting smallpox from Soviet scientists were unfounded, despite widely publicized reports by Judy Miller and others.) Other countries suspected of having inadvertently or deliberately retained specimens of the virus include China, Cuba, India, Iran, Israel and Pakistan.

Bakyt B. Atshabar, head of the 60-year-old institute that will run the new lab, the Kazakh Scientific Center of Quarantine and Zoonotic Diseases, is keenly aware of the dangers of weapons development: his father helped diagnose the effects of weapons tests on thousands of people who lived near the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site, in the north of the country.

But to him and other biologists in Almaty, the lab is less about defense strategy and more about developing scientific expertise. Currently the KSCQZD is focused on studying and preventing potentially lethal contagion, like the case of the teenager across the southern border in Kyrgyzstan, who died last week from bubonic plague after eating a barbecued marmot (he was likely bitten by a flea, doctors said).

Dr. Bakyt B. Atshabar, head of the institute that will manage the Central Reference Lab

“We’re looking forward to this becoming a regional training facility focused both on human and animal infections,” he said. “Cholera is also one of the major problems in our region, mostly with our numerous southern neighbors.” He also cited an incident in July in which Kazakh tourists returned from a trip in Southeast Asia with dengue fever.

Increased trade with its eastern neighbor China also threatens to increase the transmission of disease. “Along with the construction of pipelines,” he said, “come rodents and fleas.”

Meanwhile, the country’s meager opposition has called the lab a risk to the citizens of Almaty; the city sits in an active seismic zone, and the lab lies just outside town, and not far from a populated suburban neighborhood. Officials have countered that the building is designed to meet the city’s highest seismic standards, and will replace what a 2011 US embassy statement said were “older buildings at the institute that are not built to withstand such tremors.”

“I would say this could take just about anything,” Dan Erbach, an engineer from AECOM, the contractor overseeing the project, said during a tour of the site, which is currently a set of bulking concrete stacked three and four stories high, set atop a remediated field. “There’s more than twice as much strength in this building than any other building in the city.” (The building’s seismic standard was the result of an intervention by the government, which placed new requirements on the project before construction began in 2011. That pushed the initial completion date back a year to September 2015.)

From a security and safety perspective, the new lab represents a giant leap. When documentarian Simon Reeve visited the existing facility in 2006, he saw Soviet-era buildings and security measures not likely to intimidate a determined terrorist—or a scientist—from sneaking some anthrax or plague out into the wild. Small locks on fridges were all that kept deadly vials from a fast escape.

From “Meet the Stans” by Simon Reeve

“We’re not that far from places where terrorists groups are living relatively openly,” Reeve said. “They would love to break in here, they would love to get hold of this stuff.”

Breaches of security and competance have been a problem at U.S. biodefense labs for decades. Texas is a particular hotspot. In 2002, a renowned professor at Texas Tech was alleged to have lied about thirty vials of plague that went missing at his lab. In two separate incidents at Texas A&M in 2006, university officials failed to tell the Center for Disease Control after biodefense researchers were infected with brucella and Q fever, which has been researched as a weapon. In March, when a sample of Guanarito, a Venezualan virus, went missing at the Gavalston National Laboratory, officials cautiously blamed the apparently missing amount on a clerical error, but the incident is under investigation by the FBI.

The Almaty lab will be outfitted with safety features like double-door access zones and special containment hoods, enough to qualify it under U.S. Centers for Disease Control standards as a level 3 biosafety lab, or BSL-3 (the highest level is BSL-4). Only a fraction of the lab will be dedicated to lethal dieases and certified at BSL-3; most of the other labs at the 87,000 square foot building will be BSL-2, for the non-lethal variety.

But plague is already a focus of work at the existing lab in Almaty because it occurs naturally in nearly 40 percent of the country. (The KSCQZD began life in 1949 as the Central Asian Anti-Plague Scientific Research Institute.) Though it’s often spread by fleas, depending on lung infections or sanitary conditions, it also can be spread in the air, through direct contact, or by contaminated undercooked food. Until June 2007, plague was one of the three epidemic diseases required to be reported to the World Health Organization, along with cholera and yellow fever. The case in Kyrgystan last week underscored the regional danger of its spread among humans; there are about 3,000 cases per year.

“We will evaluate the scale of contacts, likely natural carriers of the disease, such as rivers,” Zhandarbek Bekshin, an official at Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Health, said. No border crossings have been closed, local media reported, but over one hundred people who came into contact with the teenager were hospitalized.

Climate change is also a concern at the lab. Because climate effects how plague spreads, studying the disease “can also be used as an indicator of changes to the natural environment,” Dr. Atshabar said.

For the US, however, the project is rooted in global security, and fits with its now decades-long collaboration with Kazakhstan in controlling weapons of mass destruction. In 1991 President Nazerbayev oversaw the dismantling and return to Russia of its nuclear weapons. But the country still maintains a store of pathogens that were once cherished by the Soviet military.

The secret Biopreparat program came into sharp focus in 2001, when a former Soviet official explained to a Moscow newspaper the suspected basis of an outbreak of smallpox that sickened ten people and killed three in a community on the Aral Sea: they were the accidental victims of a Soviet military field test at a bioweapons facility based on a nearby island, he said.

Because some of those sickened had already been vaccinated against smallpox, the incident raised questions about the ability of vaccines to protect against state-designed bioweapons.

With another smaller lab at a military base in the town of Otar, in western Kazakhstan on the Caspian Sea, and a flurry of similar projects in the works—in Russia, Uzbekistan, Georgia, Ukraine, Armenia, and Azerbaijan—the Pentagon hopes its Defense Threat Reduction Agency can also establish a regional early warning system for infections and outbreaks. (As the U.S. weighed responses to Syria’s use of chemical weapons this week, DTRA announced more grants for research into sensing and tracking WMD.)

Is it possible, as some Russian critics have alleged, that labs like this could serve as brain trusts and storehouses for weapons research, for either the US or their home countries? “Russia sees this as… a powerful offensive potential,” Gennady Onishchenko, the Chief Sanitary Inspector of Russia—a kind of Surgeon General—told reporters in July.

Washington denies that these reference labs and the secret research at the historic home of American bioweapons, at the US Army base at Fort Detrick, Maryland, have anything to do with offensive weapons, that they meet the standards of the 1972 Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BWC), and that their work will eventually be made public.

Funding for the $103 million construction project in Kazakhstan, and much of the lab’s operations in its early years, will come from the Dept. of Defense, which envisions it as playing a central role in monitoring pathogen outbreaks, a strategy that received new funding after the anthrax attacks in 2001. Last year, the White House announced a program that consolidated these efforts under the banner of “biosurveillance.”

“DOD’s involvement in biosurveillance goes back probably before DOD to the Revolutionary War,” Andrew C. Weber, assistant secretary of defense for nuclear, chemical and biological defense programs, told American Forces Press Service last year. “We didn’t call it biosurveillance then, but monitoring and understanding infectious disease has always been our priority, because for much of our history, we’ve been a global force.”

As the former director of the two-decade old Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Program (or “Nunn-Lugar” for short), Weber has paid special attention to Central Asia. After he spent much of the 1990s helping the U.S. remove weapons-grade uranium from the former Soviet Union under Nunn-Lugar, he was instrumental in creating Central Reference Laboratories in Almaty and elsewhere in the region.

An English-language editorial in Pravda in July referenced Weber’s role as something that should “promp[t] serious reflection.” Responding to a US State Department report that Russia was possibly pursuing bioweapons research, the Foreign Ministry in Moscow noted that it “gives impression that the US, despite the changes occurring in the world, still remains in the grip of cold war propaganda.”

Kazakh officials meanwhile underscored that the lab, which operates under Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Health, was not connected to Soviet defense research. But historically, scientists at the USSR’s anti-plague institutes—including the one that will run the new Almaty lab—were also involved in a secret project to design vaccines for pathogens that had been modified by the military program that Dr. Alibek, the defector, once ran.

On the sunny day earlier this month when we visited the site, however, the conversation was focused on saving lives through cooperation, not the opposite. The hope is that labs like this will simply encourage more international scientific relationships, the kind that build cultural trust, and the kind upon which science thrives.

Despite “typical intergovernmental issues,” Carlton and other officials expressed optimism about the collaboration. “I never like to refer to this as the former Soviet Union. That was in the past. In the military, it’s been a sea change in our mentality.

“Kazakhstan has come so far in terms of government organization, and understanding the threat and the problem,” he added. “This is a country that willingly said, we want to get rid of this threat and take the lead. Kazakhstan has opened up as an exemplar around the world.”

This story was reported as part of an International Reporting Project fellowship. It was republished with permission from Motherboard. Follow Alex Pasternack on Twitter

No comments:

Post a Comment