↰al-Tantura - الطنطورة: al-Tantura Massacre & Ethnic Cleaning Are Exposed: 21 eyewitness testimonies of war crimes against humanity

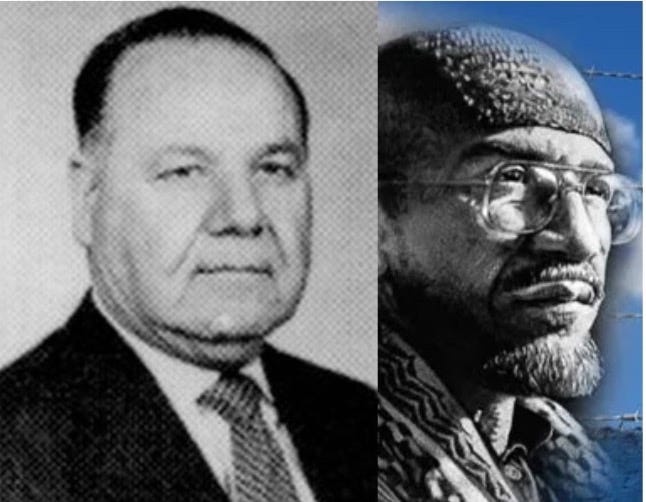

Muhammad Abu Hana, born in 1936, resident of the Yarmuk camp

We were awakened in the middle of the night by heavy gunfire. The women began to scream and run out of the houses, carrying their children, and gathered in several places in the village. I went out of the house too and began running around the streets to see what was going on. Suddenly a woman shouted to me: "Your uncle is wounded! Quick, bring some alcohol!" I saw my uncle bleeding heavily from the shoulder. Being young, I was unconscious of danger. I grabbed an empty bottle and ran to the dispensary nearby. Zahabiyya, the nurse, was there. She was one of the Christians of the village. She filled the bottle with alcohol and I ran back to my uncle. The women cleaned the wound and took my uncle to our house where he hid from the soldiers in the grain attic. But the soldiers saw the trail of blood and soon burst in, asking my grandfather where my uncle was. My grandfather said he didn't know. They left but came back several times with the same question. At some point my uncle, who was in pain, asked for a cigarette and my grandmother gave him one. When the soldiers came back again the smell of the tobacco guided them to him. They took him away. On their way out they insulted my grandfather and called him a liar, and he answered back that anyone would protect his own son.My uncle survived thanks to the intervention of the mukhtar of the Jewish colony Zichron Yaacov. He had good relations with my grandfather, who was the mukhtar of Tantura. At 9 in the morning, the shooting stopped and the attackers rounded everyone up on the beach. They sorted them out, the women and children on one side, the men on the other. They searched the men and ordered them to keep their hands above their heads. Female soldiers searched the women and took all their jewelry, which they put in a soldier's helmet. They didn't give them back when they expelled us towards Fraydiss. During the entire operation, military boats were offshore.

On the beach, the soldiers led groups of men away and you could her gunfire after each departure.

Towards noon we were led on foot to an orchard to the east of the village and I saw a bodies piled on a cart pulled by men of Tantura, who emptied their cargo in a big pit. Then trucks arrived and women and children were loaded onto them and driven to Fraydiss. On the road, near the railroad tracks, other bodies were scattered about.

Muhammad lbrahim Abu' Amr, born in 1935, resident of the Yarmuk camp

We had gathered at the center of the village, in the house of Hajj Mahmud al-Yahya. When the village fell and the soldiers entered, they herded us to the beach. On the way, near the house of Badran on the street leading to the mosque, I saw the bodies of seven young people from the village. A woman, 'lzzat Ibrahim al-Hindi, started to scream, but a burst of gunfire silenced her for good. This woman was the mother of the martyr Abd al-Wahhab Hassan Abd al-Al, who had been killed during an attack with explosives by the Jews of Haifaat the end of 1947 (*).When they loaded us onto trucks, we saw bodies piled along the road like stacked wood. A woman recognized her nephew among the dead--it was Muhammad Awad Abu Idriss. She started to scream. She didn't know yet that her three sons had met the same fate. Her sons, Ahmad Sulayman, Khalil, and Mustafa, had been killed, but we only learned this later, in exile. But the mother always refused to believe it, and insisted that they had escaped to Egypt and would come back to find her one day. She spent the rest of her life waiting for them.

* A series of bombing attacks known under the name of "Massacre des halles"

Salim Zaydan Umar al-Sarafandi, born in 1932, resident of the Yarmuk camp

The soldiers laid siege to the house where we were gathered. They fired for a long time inside the rooms and made us come out. Then they led us to the beach. The morning of the next day, a Jewish officer came, I think his name was Samson, with a list of names of men from Tantura. He started calling them one by one and asked everyone who was present to hand over the weapons in their possession. Then they led several of the men away to look for arms. Some of them did not come back.They called the name of my brother, Abd al-Rahman, but then decided instead to have my father accompany them to our house to search for weapons, even though he said he didn't know anything about any weapons. In the meantime my brother, who was near them, his arms bound with his jacket, heard them discussing whether or not to kill my father. At this point, a Jewish colonist from Zichron Yaacov, who had a plot of land next to my father's and had good relations with him, intervened and it's because of that that my father's life was spared.

Four men from our group were led away to gather the bodies scattered around the streets. We didn't know what happened to them. At the beginning of the afternoon, they made us walk from the cemetery towards Zichron Yaacov. We didn't know anything about what happened to the women and children either. At Zichron Yaacov, they put us in an abandoned British police station, about thirty to a room, without food or water, and struck us and insulted us. I even saw a soldier go crazy beating Dib al-Dassukii on the head with the butt of his rifle, and he was bleeding profusely.

A few days later, they transferred us to an Arab village emptied of its population (Umm Khalid) and surrounded with barbed wire! From there, we were taken to a large prison camp set up in the village of Ijlil near Jaffa. We received 150 grams of bread and a ladle of lentils or chick peas a day. They put us to work. Those between the ages of 15 and 17 had to clean and work in the camp's offices, while the older ones had to carry construction materials for fortifications, dig trenches, and bury the dead of the Arab armies. We were the ones who buried the martyrs of the Iraqi army in the village of Qaqun after it fell to the Israelis.

Later I was transferred, along with a number of others from Tantura, to the prisoner camp inSarafand. This took place after about 25 inhabitants of Tantura had managed to escape from the Ijlil camp. I spent an entire year in Sarafand.

One day, the commander of the camp charged one of the Arab prisoners to ask us about sums of money we might have left behind in Tantura. He promised to share the booty if we told him where the caches were located. I knew that my mother had concealed some money and a few pieces of gold in two hiding places in our house, and I told myself that if I mentioned this I would at least have the chance to go with him to see Tantura again and possibly get half my mother's money.

We climbed into the commander's vehicle. Another officer with three stripes went along. The houses were all destroyed. When we got out of the vehicle, I was surprised that the officer gave me an old rusted revolver: "Here, if other soldiers here ask you what you are doing in the village, tell them that you had hidden this revolver and that you led us here so you could hand it over." Then he threatened me about what would happen if I spoke to anyone about our affair and the true reason for my presence in the village.

The two hiding places were empty, and we came back to the Sarafand camp where I remained until the end of 1949.

Amina al-Masri (Umm Mustafa), Tamam al-Masri (Umm Sulayman), born in 1925 and 1927, respectively, residents of the Qabun quarter of Damascus

From the time that the village of Kafr Lam was captured after the fall of Haifa, we began to fear an attack on Tantura. The night of the assault, men were on guard duty at the various entrances to the village, but they were poorly armed. I heard gunfire and thought it came from the "Gate" [al-Bab], that is to say from southeast of the village. I woke up my husband. At first he thought I was dreaming, but the firing intensified and there were explosions and all. They came from the hill of Umm Rashid in the south and from the direction of the Tower, on the coast to the north where the Roman ruins are located. We got the children out and went to my parents' house. They were terrified. The shooting had died down a little and people thought that the battle was over. How naive we were! To the point that Abu Khalid Abd al-'Al, thinking that the Jewish attack had been countered, cried out: "We won! We got them!" A few minutes later the gunfire resumed with a vengeance, accompanied by shelling. People began running in all directions shouting, "We saw them! ! The Jews are in the village!!" The day had broken by the time they led us to the beach. I saw the Jews kill Fadl Abu Hana at the place they call the Marah. Fadl was unarmed, but he was dressed in khaki. Then, before our eyes, they took a first group of men whom they shot, all except one who they told: "Look hard and then go tell everyone what you saw."In their search for money and gold, they even went through the swaddling clothes of our infants, and when a little girl tarried in taking off an earring, a woman soldier ripped it off and the little one began to bleed.

They then herded us to a piece of land that belonged to the Dassuqi family. We had walked there barefoot over stones and brambles, and then they loaded us onto trucks which took us to Fraydiss. There, my grandfather, Hajj Mahmud Abu Hana, sensing that his end was near, sent one of his daughters to find him a shroud in 'Ayn Ghazal or Ijzim, but she returned empty handed. He drew his last breath after having recited two rak'a and read verses of the Koran. He had called upon God not to let him die outside Palestine. We then found a coverlet, took out the wool and made a shroud with the material, so we could bury my grandfather.

In Fraydiss, a military vehicle driven by a female soldier purposely ran down a woman ofTantura, Amina Muhammad Abu 'Umar, the wife of Falih al-Sa'bi, who had been returning from the field with a bundle of wheat on her head that she had gathered to feed her children. A woman who witnessed the scene rushed to pull the dead woman off the roadway. Another vehicle barreled towards her, missing her but running over the dead woman a second time.

That day, I told myself that the End of Days had come and that none of us would survive these events.

We spent a month in Fraydiss. A child was born there, the first child of Tantura born after the massacre. The family, the Abu Safiyyas, had lost most of their men folk the day the village fell.

Farid Taha Salam, born in 1915, resident of the Qabun quarter, Damascus

After we heard the news that Haifa and the surrounding villages had fallen, we took up a collection to buy arms. What we had was a few rifles and one automatic weapon, a Brenn. Most of the weapons were English, guns that had been owned by the policeman demobilized by the English. We also had a few hunting guns.We organized ourselves for night watches but had more men than guns. The guard posts were Qarqun, Tallat Umm Rashid, the water tower, the church, al-Bab, al Burj, al-Warsha. (check last three?). At each of these places, there were only a few men, because we didn't have weapons for everyone. Our training didn't go beyond the stage of assembling and disassembling rifles, and even then," those who could do it were considered professionals. In fact, the men among us that were relatively trained were those who had served in the English police.

When the attack began, our guards returned fire until the ammunition ran out. One would have to say also that the lack of experience contributed in that our men wasted ammunition. Some of the defenders fell back towards the center of the village, others managed to get out of Tantura, and a third group, finally, remained in place. Some of those were cut down fighting, others were taken prisoner and liquidated by the attackers.

The population had been rounded up by the victors, and groups of men were led away one by one, and we didn't know their fate. I remember that the last group counted about forty men. One of the men led away by the attackers was Taha Mahmud al-Qasim, who came back afterwards and told us that a Jew had asked the group: "Who here speaks Hebrew?" When Taha said he did, the Jew had added: "Watch how they die and then go tell the others." Then they had lined up the other men of the group against a wall and shot them.

Later Yaacov, who was the mukhtar of Zichron Yaacov, came on the beach where we were being held. My father, who knew him, said: "Abu Yussef: the village has fallen, and you have taken all the weapons. What more do you want?" He replied: "Taha, we have to reconcile you with the Haganah in order to be able to stop the fighting."

Later, when we were prisoners at the Sarafandcamp, I got to know a young Jew who must have been about 17 years old. One day I said to him: "Where are you from? Why did you come to Palestine?" He told me he had come from Russia and added: "If someone hears that he now has a State, who wouldn't rush to go there?" I then remembered Rothschild, who had visited Tantura one day in the 1920s. When he found only Arabs there, he reproached the Jews of Zichron Yaacov because they hadn't succeeded in buying any of the land of our village. Even Musa, who was Jewish, who had come to our village, who had lived there, worked the land, built a house there, and whom we called "Musa the Tanturi"--even he left because he felt like a stranger among us.

Musa ' Abd ai-Fattah al-Khatib, born in 1924, resident of Yarmuk camp

The night of 23 May 1948, Muhammad al-Hindi, who was the head of the guard of the village, had me called to take position at Dabbit al-Bi'r, between the water tower and the school. There I found Issa al-Fakhri, who had a hunting rifle, Abd al-Jabbar Taha al-Shaykh Mahmud, who had a Gennan rifle and 50 bullets, the son of the Mukhtar of Cesaree, also armed with a hunting rifle, and Hasan Faysal Abu Hana, who was unarmed.I had an English gun and 75 bullets. At midnight I gave my weapon to the man who came to replace me, and I was about to go home when ' Abd al-Jabbar suddenly told me to listen: Voices speaking in Hebrew reached us from the field close by. We left our position and crept towards the field to investigate. Suddenly a volley of fire rang out from the direction of the water tower and Qarqun. We hastily regained our position and started firing towards the fields in the east.

After a few minutes, we thought that the attackers had withdrawn. But then we saw vehicles unloading armed men near the school, and the attack on this last position began. We were a few dozen meters from the school and at one point I thought that our position there had fallen. Then I saw military vehicles advancing from al- Bab.(*)

Abd al-Jabbar and I thought the village had fallen. It was then that' Abd al-Ralnnan Zaydan reached us with 300 bullets that he gave me. I stopped firing to take stock of the situation. I then heard Faysal Abu Hana say to Issa ai-Hamdan: "Brother, I'm hit, I'm dying." Sulayman and Ahmad al-Masri came at that moment and said they were going back into the village to see what was happening. I warned them, but they left anyway and never returned. Later I learned that they both were killed.

Soon 'Abd al-Jabbar had only 5 bullets left. There were only three of us now, and we had only one gun. An armored vehicle started coming down the dirt track nearby and we thought we had been spotted. Two men got out, and we fired on them and hit them. A second armored vehicle with a white flag approached and they tried to pick up the two bodies but couldn't because we were firing on them with our only gun. Then intensive shelling of our position began and the armored vehicle pulled off the dirt track and onto the plowed fields. A man from the village had hidden himself under some straw, and the vehicle crushed his leg but he didn't [make a peep, sound] even cry out so as not to be discovered. It was then that I suggested to 'Abd al-Jabbar that we change position. We came back to the first hill, where Isa al-Hamadan joined us. The soldiers were advancing towards us. Isa asked me for my gun and gave me his, which had jammed, so that I could try to get it working again, but I couldn't. That's why it was Issa who, after taking cover, began firing on them. Little by little, we were falling back towards the water tower. We reached a cave where we found 'Atiyya 'Amshawi and Muhammad Shihada. We remained there until 9 in the morning, when we left our two comrades and advanced towards the water tower a few dozen meters from the cave.

Suddenly I heard Hebrew and someone say to 'Abd al-Jabbar: "Hands up!" We hit the ground instantly and managed to get to a crevasse in the quarry, where we hid, immobile, invisible from their side. But Isa had continued to fire on them until he was out of ammunition. They ordered him to put up his hands and asked where the other gunman was. He said he was alone. They asked if he had served with in the British police. He said yes. Then they ordered him to undress and led him to an unknown destination.

Soldiers had taken position up a few meters from our hiding place. We held our breaths. At sundown, they abandoned the position and moved in the direction of the water tower. We then decided to try to make it to the village of Fraydiss, where 'Abd al-Jabbar's uncle lived. That's where we learned the fate of our village. We remained three days at Fraydiss, spending the day at Mount Cannel and the night in the village, then we left for 'Ayn Ghazal where we found others who had withdrawn fromTantura-- 'Ali Taha, Nimr al-Jammal, Mahmud ' Abd al-Rahim, Yahya al-Hindi, and Kamil al-Dassuqi

* The only road in the village suitable for motor vehicles, because it let into Haifa-Jaffa road.

'Adil Muhammad al-'Ammuri, born in 1931, resident of the Yarmuk camp

Lots of things happened before the attack on Tantura the night of 23 May 1948. I especially remember watching the train go by loaded with armored vehicles, supplies and ammunition for the colonies of Khudeira, Rmat Gan, and Netanya. During the same period, armed men would fire at Tantura villagers working their fields. It was during such an incident that As'ad Abu Mdayriss was killed.The night of the attack, I was in our house at the center of the village. I tried to go to the southern part but was stopped by machine gun fire. People were rushing about, old men and children, asking God to give us victory. They weren't so much in a state of panic as lost, not knowing what to do and what was really happening.

During the earlier clashes, the villages of the Haifa district had gone to the aid of the others. This time, we thanked God that the neighboring villagers didn't come, because they would have been cut down in ambushes at the Israeli positions set up on all the roads leading to our village. Later I learned that the inhabitants of Jaba and 'Ayn Ghazal had nonetheless tried to come to our aid but had been unable to reach the village.

When they rounded us up on the beach, the Jews had asked us: "Are there any Syrians among you? Have you received Syrian help from the sea?"

Once we were captured, when they transferred us from the camp at Umm Khalid to the Ijlilprison camp, the Red Cross representative registered our names and informed us of our rights as prisoners of war. The soldiers then made us harvest the Arab fields on behalf of a Jewish army contractor. They paid us with coupons that enabled us to get food items at the cantine to satisfy our hunger because our daily prison rations were woefully insufficient. One day, several buses arrived in the camp loaded with men. They made them get down so they could drink at the camp's only water faucet. Because they were parched with thirst there was a real crush to get to the tap, and the soldiers opened fire on them and blood mixed with the water. Tens of men fell dead before our eyes. It was only later that we learned that the men were from Lydda and Ramla.

When we left the camp for exile, we had to cover the distance between Wadi al-Milh and Jinin (*) by foot. I saw numerous Arab corpses along the road.

* About 40 kms

Mahmud Nimr 'Abd al-Mu'ti, born in 1930, resident of the Yarmuk camp

My father and I alternated shifts on guard duty. The night of the attack, it was my father's shift, and he was posted at Qarqun, south of the village. In the morning when I left the house people were running in all directions, congregating in groups. I ran into Muhammad Shihada who gave me a rifle and told me that our position at al-Warsha had not yet fallen. I ran to join the defenders.On the road, my uncle stopped me and told me that al-Warsha had fallen. We returned to the village and he hid my weapon in the tomato patch inside the house compound. When we came out we were surprised by Israeli soldiers who we met face to face. They searched us and confiscated my identity card as well as 7 Palestinian pounds. They took me and other prisoners to bury our martyrs, one of whom was Mustafa al-Salhud. Later I learned that they had already killed his two brothers. One of those who had been spared was Taha Muhammad Abu Safiyya, but when the sent him back his hair had turned whit, even though he was only 16. On the road leading to the cemetery, I saw a number of bodies that I was not able to identify.

I also remember seeing an old man from the Yahya family known as Abu Rashid. He had been badly wounded and had leaned up against a stack of sugar cane. He died in a sitting position and seemed to be alive, and it looked like he was smiling. I saw one of the Jewish soldiers take a picture of him.

Later, they locked us up in the prison camp at Ijlil and profited from us by making us harvest the fields. We were well aware that a number of those who went to work didn't come back. Before Ijlil, we had been imprisoned at the camp in Umm Khalid. There, one day they ordered us to dig a big pit, which we did under their guns. They were talking among themselves in Hebrew, and some of us understood that they were talking about finishing us off. One of us managed to get word to the camp commander, who immediately had our guards replaced.

One day they took us to the village of Qaqun, where the stench was overpowering because of the corpses.(*) We began digging a hole to bury the dead, but suddenly an Iraqi mortar shell landed nearby--the Iraqis were positioned 5 kilometers from there. A Jewish soldier was killed. I myself was hit by shrapnel but I didn't realize to what extent until Isa Abd al-'Al told me I was bleeding from my hand, chest, and shoulder and I lost consciousness.

They treated me along with their wounded and plastered my arm. The Red Cross visited us a little later in the camp. They asked me about my wound. The man in charge of the camp, whose name was Punstein, said that I had been wounded while fighting against his men in Tantura. But the Red Cross delegate was not satisfied with his answer and asked if any of us spoke English, and Fuad al-Yahya told him what really happened.

The Red Cross then told me that I was to be freed, but at first I didn't believe it. As for Fuad al-Yahya, he was punished for speaking up.

The men from Tantura started writing letters to their loved ones. But I was at a loss--where to hide all these letters? My clothes were in rags and the only pocket was small. One of my companions suggested my arm sling, and that's where they were hidden.

The Red Cross turned me over to the Iraqi army, which closely questioned me. How many Iraqis had been killed at Qaqun? How many tanks did the Jews have? How many machine guns, how many artillery pieces?

I was afraid that they would discover the letters, since it was very easy then to be accused of espionage or working with the enemy. Once I was released, I managed one by one to get them to the addressees. I remained in Jordan into 1949, and then we were moved to Syria.

* He refers to 90 Iraqi officers and soldiers who fell defending the village

Muhammad Qasim Daqnash, born in 1924, resident of the Yarmuk Camp

The night of the assault on the village, I was south of Tantura, in position at Tallat Umm Rashid. I was armed with a hunting rifle. My father was next to me. When the shooting began, my father took my gun and ordered me back to the house; he feared for my life because I was at the center of a family feud in the village.I ran into a group of villagers near the school. One of them had a Brenn automatic rifle (fusil mitrailleur). They told me that Ibrahim al-Shuri had been hit. Lutfi Dassuki was the one with the Brenn. He said: "Who wants to go to the front line?" I remained silent because I was afraid and as if in a state of shock.

In the southern part of the village, I saw the child Tawfiq Hassan al-Hindi, who was wounded, being carried into one of the houses.

When the attack became more intense, several men --Mahmud Abu al-Nada, Yusuf Fayiz Ayyub, and one of my cousins--took cover in the house of Muhammad Abu al-Nada. My cousin was hit by a bullet. And when his father leaned out of the window to see what was going on, he was shot dead.

Once we were rounded up on the beach, the Jewish soldiers led Shaykh Rushdi al-Jayyshi and a young girl from the Jisr al-Zarqa Bedouin to convince a group that was continuing the fighting that if they gave themselves up no harm would come to them. When he returned, the shaykh told us that no sooner had the group surrendered than two of them had been shot in cold blood on the spot and finished off with bayonettes. The shaykh was overwhelmed with remorse for having been used that way.

We were led to the prison camp in Umm Khalid. There, two men of the village, Muhammad al-Malah and' Arif Taha Salam, managed to escape through the little window of our cell.

Later we were transferred to the prison camp at Ijlil I decided to escape by any means. One day five of us eluded the guard's vigilance and escaped--Muhammad 'Amshawi, Ibrahim al-Shuri, Muhammad al-Jammal, Fawzi al-Tanji, and myself. We hid in a nearby orchard and heard the Jews go through the rollcall and then we heard someone cry: "Five missing!"

That night, we started walking towards the village of Jalulya, then towads Bir al-'Adss and from there to an Iraqi army position.

The Iraqis drove us to Qalqilya. From there, we were transferred to Nablus for an identity check. None of us had any papers and they asked us if anyone knew us in Nablus. I proposed to the officer that he let me go to find someone. He started laughing and said: "One bird vouches for an other and the two flyaway." We remained like that until an officer realized the situation we were in. He vouched for us and we were released.

Rahma Salih Abu Salim, date of birth unknown, resident of the Yarmuk Camp

At dawn, my mother told me: "Go to the chicken coop and let the hens out." The chicken coop was behind our house. I heard shooting but I didn't realize that it was the war. I saw the Jews coming. I ran to my mother, and we left the house to gather with other people of the village.

On our way, I saw a woman from Fraydiss, who was in Tantura that day by chance with her husband. The Jews had shot him even though he was unarmed. They had put sand in his mouth and kicked his corpse. The woman was weeping, throwing stones at them and shouting insults.

Yusuf Mustafa al-Bayrumi, born in 1928, resident of Yarmuk Camp

After the fall of the village, the survivors were rounded up and the men led into captivity. I ended up at Sarafand. There were some men from Jaffa with us. Once, returning from work, we noticed that a young prisoner hadn't come back. His name was Khalil al-Tartir. We later learned that they killed him because he had supposedly tried to flee. After this murder we refused to work outside the camp. We feared for our lives and we demanded the presence of the Red Cross.One day while we were in the Ijlil camp, some Jewish cavalry troops arrived. They started take pictures o us. I asked one of them: "When are you going to let us go back to Tantura?" To which he replied: "The day you can see your ears with your eyes is the day you'll seeTantura."

Ali Mustafa al-Bayrumi, born in 1938, resident of Yarmuk Camp

I was very frightened by the heavy gunfire. At dawn, my brother wanted us to go to the center of the village to be better protected. My father said: "Here we were born, here we die." He thought my brother was trying to get us to abandon our village. On the road, I saw the bodies of the children of lsa al-Hamdan lying on the ground.

About a week before the attack, large boats were moored avaient acoste near the village to evacuate the population by sea. But the men of Tantura refused to leave and some of them even fired at the boats, forcing them to lift ancre. We later learned that the boats had come from Lebanon, sent by the Arab High Committee which, since the fall of Haifa in April and the proclamation of the State of Israel on 14 May, feared for our lives.

Yahya Abu Madi, born in 1931, resident of the Yarmuk camp

After the fall of Haifa and the surrounding villages, followed by the proclamation of the state of Israel, the attack on Tantura seemed inevitable. The men had very few weapons, and they were neither trained nor organized. They kept guard at the entrances of the villages, in the fields and bills. Our house, which was in the sector called al-Ramla north of Tantura, was relatively isolated.The village fell quickly, and the soldiers entered the village. At this stage, anyone who crossed their path got shot. Once they rounded us up on the beach, people began exchanging the names of the dead. Then I heard one of the new arrivals call out for 'Abd al-Latif Suwaydan: "Your father was shot." The Jews then brought a Hotchkiss machine gun, loaded it and turned the barrel towards us. Everyone thought that this was the end, but instead they led groups of men away to an unknown destination. It was only later, at the end of our captivity, that we learned that two hundred of our brothers from Tantura had been massacred.

In captivity, we found ourselves with other Palestinian villagers. There were also some non-commissioned officers and soldiers of the Egyptian army. At Sarafand camp, the Red Cross visited us and allowed us to write to our families, a maximum of 25 words per person.

The head of the camp was named Eliahu. One day he came to us with a photo in his hand. He asked for those from Tantura to identify themselves. Lutfi Dassuki raised his hand. Eliahu asked: "Do you know this man?" Lutfi replied: "Yes, it's the photo of Yaacov, mukhtar of Zichron Yaacov." Then Eliahu said: "You should all kiss his hand, because without his intervention the whole population of Tanturawould have been executed."

After our liberation, I learned that the massacre ended because the Jews had heard that Abdallah al-Tall (*) had just captured 300 Jews at Kfar Etzion so it would be useful to leave us alive for future prisoner exchanges. Still, I don't deny that Yaacov, the mukhtar of Zichron Yaacov, was compassionate and that he didn't like bloodshed.

* One of the commanders of the Transjordanian units operating in Palestine.

Yusuf Salam, born in 1924, resident of Yarmuk camp

A week before the attack, my brother Mustafa and my cousin Muhammad, who were staying with some of relatives at Kafr Lam, were killed by the Jews who attacked the village. My father was wounded while trying to bring back their bodies.I was awakened by the sound of bullets. I asked my aunt, who was staying with us to take care of my wounded father, what was happening. She said: "Don't worry, it's not very serious." I saw them enter the village and even though a white flag had been hung from the minaret of the mosque, they killed every man who crossed their path.

While we were being held on the beach, and after they had selected a last group of about forty men for execution, the mukhtar of Zichron Yaacov arrived and spoke to Samson (*) in Hebrew and warned him against killing them. Samson replied that he had orders to kill the whole lot. Yaacov left and soon returned with a piece of paper that he handed to Samson. That's how this last group escaped death.

Besides the bodies that I saw in the mass grave that had been dug in the Dassukis' field, I myself counted 25 bodies of our people.

In Umm Khalid, the deserted village they had transformed into a prison camp, some people from Zichron Yaacov came one day and tried to convince the head of the camp, whose name was Ashkenazi to treat us more kindly and with less insults and humiliation, but he refused to listen and made them leave.

It was in Umm Khalid that. Arif Salam and Muhammad al-Malah managed to escape, so they decided to punish us collectively. We were then transferred to Ijlil. One day, a soldier started shooting at the prisoners and a number of prisoners were killed. Yusuf Abu Ajjaj was one of the victims. Later we learned that the soldier wanted to avenge the Israeli losses at the battle of Tirat Bani Sa'b against the Iraqis.

Another time, the guards became very nervous. A group of Irgun wanted to occupy the camp to liquidate all the Arab prisoners. I remember hearing threatening words between the Haganah and the Irgun people at the entrance of the camp.

When I learned from my comrades that the Jews were taking prisoners to work outside the camp and that a number of them never came back, I resolved to escape. So one night I went near the bungalo of the the Egyptian prisoners because it was unlit. Three other prisoners had decided to try to flee with me: Anwar Farhat, Abroad' Ammuri, and a man from the village of Yazur. We were counting a lot on the one from Yazur because he knew his way around the area. Three rows of barbed wire surrounded the camp and my companions held back. I got through the first row without difficulty. My face and chest got cut up going through the others, but I plunged ahead until I got out. I had no idea about the region and the weather was cold and wintery. I wandered aimlessly around for three days until I was stopped by soldiers who turned out to be Iraqi. A Palestinian was with them who knew my village and confined my account of what had happened. They took me to Tirit Bani Sa 'b. When the villagers saw me coming, bleeding and accompanied by soldiers, they thought I was a prisoner captured by the Iraqis and tried to attack me, but an officer stopped them.

Life was not easy there, either. There wasn't enough food, and no clothing.

* The leader of the attackers

Muhammad Kamil al-Dassuki, born in 1935, resident of Raml camp, Lattakieh

I heard people cry: "The Jews are attacking, the Jews are attacking!" Bullets were whistling and you could hear the explosions in the village. At dawn, I saw boats unloading soldiers near the Burj, north of the village, and they advanced towards the various entrances of Tantura. While we were carrying the dead, I heard a young man crying. A soldier asked him why he was crying. He said: "My two brothers have been killed. Here's the body of my brother Khalil, and here is my brother Muhammad. My mother has no one but me now." "What use is your life then?" the soldier asked. And he shot him The boy's name was Mustafa al-Salbud.In the cemetery, I saw cars filled with Jews, some of them laughing and singing, but others were terribly silent.

When we were rounded up on the beach, young Jews, boys and girls, climbed onto the village fishing boats on the beach and began crowing their victory, while their chief, a tall man with pale skin, asked us: "Where are the Syrian soldiers? Were you fighting alone?" Later, he turned us--that is, the women and children--over to the mukhtar of the village of Fraydiss. The people of Fraydiss welcomed us as best they could, and the people of the nearby villages of Jaba', Ijzim, and ' Ayn Ghazalsent food and blankets for us.

We spent a month at Fraydiss. One day, an old Jewish man came to the village. He gathered all the boys between 12 and 14 and led us to Tantura to harvest the garlic and potatoes, under the guard of Jewish soldiers.

A soldier asked me: "You're from Tantura. Do you know someone from the Dassuki family? -"Me," I replied. "Do you know Abu 'Aql?" "He's my mother's brother." He put down his rifle and said: "Where is he?" I said he was at Fraydiss. He then started to cry: "Greet him for me. I know him, I'm the son of Abraham Hallaq, the train conductor on the Haifa-Jaffa line and my father is a friend of your uncle!" Then he asked after my cousins and I told him that Salim and Nimr had been shot. He immediately cursed the murderers and added, "Me, too. Two of my brothers were killed." Later, he came to Fraydiss to visit my uncle.

My father, who was one of the defenders of the village, had managed to get to ' Ayn Ghazal. I decided to try to join him I started walking, barefoot. When I got to my father, a man from 'Ayn Ghazal, Hajj Hasan, seeing that I was barefoot, took me with him and bought me a pair of shoes.

Abd al-Razzaq Nasr, born in 1931, resident of Raml camp, Lattaquieh

The night of the attack, I was on guard duty north of the village, at Bi'r Jamus, not fur from Dibbit al-'Ijra. Shots rang out, coming from the south near Talat Umm Rashid, and then got closer to our position. About 2:30 in the morning, a train brought soldiers who took position above us, where they started firing and shelling us. We attempted to withdraw, but lost two men. I stayed with Muhammad' Awad. During our failed retreat, I saw two other bodies, including that of Muhammad Shihada. When we got near the Burj, we passed a group of our people-- if my memory serves, there was Hassuna Sa'id Salam, Hadi Abu Ghazala, Abu Subhi ' Ashmawi, Hajj 'Abd al-Rhamn Dassuki, and Fayiz Ayyub. Hajj Dassuki was wounded in the head and Sa'id Salam in the shoulder. I tried to help them. When we got near his house, near the Marah, the Hajj asked us to leave him there. It was about 6 in the morning.I went home and hid my gun, and asked where people were. I learned that many were at the house of 'Iqab al-Yahya but that the soldiers had found them there. They had burst through the front entrance facing the sea and the back door at the same time, firing in all directions and shouting: "Get out, out!"

Everyone was herded to the beach. Their officer, Samson, came and asked for Muhammad Yusuf al-Hindi. He put a revolver to his temple and asked where the village weapons were hidden. Muhammad was forced to give a few names, including mine. They led me, my arms tied with my shirt, so I could find my rifle and they took it. On the way I saw a number of bodies near the Abu Safiyya house, and on the way back, at the place called Marah, I recognized the bodies of Fadl Abu Hana, Fawzi Abu Zamaq, and Muhammad' Awad Abu Idriss. In the little ally by Abu Juayd's barber shop, I saw a long trail of blood running some 20 meters to a little place were more than ten bodies had been piled up.

'Abdallah Salim Abu Shakar, born in 1931, resident of Lattaqieh

Tantura is on the coast, about 30 kilometers south of Haifa. Between the village and Haifa there were a number of villages, all Arab. Tantura 's lands were fertile and well irrigated, covering more than 12,000 dunams.

The village had a primary school for boys and another for girls, as well as a dispensary. Doctors took turns visiting the village regularly, and a nurse was there all the time named Zahabiyya. We also had a cultural club and a sports club. A little before the attack on the village on 22 May, the Jews asked us to accept the fait accompli, to recognize the State of lsrael and to turn over our weapons. The man who brought us this message was a Palestinian from the village of Fraydiss who had been charged with this mission by the mukhtar of Zichron Yaacov , who was conveying the orders of the Haganah. The inhabitants of Tanturarefused.

After the fall of St.-Jean Acre and Haifa, some of the inhabitants of Tantura did leave, by sea, for temporary refuge in Lebanon. This was mostly women and children and a few old men. The others decided to stay and face the unknown fate that awaited them.

The village did not really have arms and the men were not organized. My father, Salim, had earlier gone to Lebanon with Wadi al-Hindi where they met the mufti of Palestine, Hajj Amin al-Husseini, in Chtaura and Mu'in al-Madi in Beirut to try to get weapons. But the response was "There is no force but that of Godil n'y a de force qu'en dieu" They continued to Syria, to Hama and Aleppo, where they succeeded in buying a few guns as well as an automatic Brenn fusil mitrailleur. You have to keep in mind that the inhabitants of the village believed at the time that they only needed to hold out for a short while, just enough time for the Arab armies to arrive.

The Jews killed my father in a house south of the village. We didn't know what happened to the men who had been posted at the entrances to the village until after our release from captivity. They led me with other young people near a village shop and lined us up against a wan, ordering us to keep our hands up. Then they took us to the beach. There we were again rounded up, about 400 men, and taken to the prison camp of Umm Khalid. When I was freed, I rejoined my family in Syria.

There still has not been an accounting of our dead, but we know that the number exceeds two hundred.

Sabira Abu Hana, born in 1933, resident of Raml camp, Lattaqieh

We had spent the evening at our neighbor's, Umm Khalid, the wife of Sa'd al-Din Abu al-Hasan. We were preparing the charcoal fire to do the laundry, because in the morning we had to help with the harvest. Nimr Frahat suddenly burst in and shouted: "What are you still doing here? The Jews are already at Tallat Umm Rashid!". We ran towards the center of the village where my maternal uncle, Sa'id Salam, had his house, and we stayed there until 6 in the morning. An hour later, I saw a Jew herding a man of the village at gunpoint.My grandfather, Mahmud Abu Hana, was shot in front of the entrance of the house. My paternal uncle, Fadl Abu Hana, was liquidated after the fall of the village and rolled in a straw mat. On the beach, they stole twelve gold bracelets from Hajja 'A'isha, the wife of lssa 'Abd al-'Al. Amina 'Awad Abu Idriss discovered the body of her brother near the cemetery. She smoothed his hair, kissed him and yelled her grief.

I saw about fifty bodies at the cemetery. I also saw Abu Jawdat al-Samnra carrying the body of his son on a ladder he was using as a bier.

After our departure from Tantura, we lost another 40 of our people, mainly children, on the road between Fraydiss and the towns of the West Bank, including Tulkarm and Hebron. Every hour someone would announce that the child of so and so had just died. I remember that in the cave of Dayr al-Moscobiyeeh alone, we buried about twenty of our bodies.

What happened to our village isn't less horrible than the massacre of Dayr Yasin, but at the time the Palestinians were more preoccupied with the fate of the living than of the dead and, soon, the loss of the country overwhelmed the loss of people and no one talked about the massacre of Tantura, until recently.

Yusra Abu Hana, born in 1915, resident of Yarmuk camp

The shooting began near midnight. Mudallala arrived from Zulu£ She told us: "Isa Dassuki is wounded, perhaps dead. And when Su'd al-Filu ran to him to give him something to drink, they fired at her and killed her."

One of my brothers, Fadl was also killed; the other, Faysal, was wounded. He had hidden in the stable but he was caught: he was smoking and the odor of his cigarette gave him away. They wanted to kill him but the mukhtar of Zichron Yaacov, who had good relations with my father, interceded for him. It should be remembered that we treated the people of his colony well when they came on the beach of Tantura.

Hasan 'Ammuri was an only child and his mother had been 45 years old when she gave birth to him. He took part in the fighting. They promised him his life if he surrendered, but they shot him the minute he gave them his weapon.

On the beach where we were assembled, they stripped us of everything: watches, bracelets, money, identity papers. On the way to the beach, the door of one of the houses was open and I saw a pile of bodies inside. Not to mention the people they had gathered and executed in the cemetery. More than fifty. All the ones they killed had no weapons, shot down in the streets of the village or inside houses. On the beach, they led men away in groups but no one came back. Towards noon, the killing ended when the mukhtar of Zichron Yaacov came with a written order. A group of some 40 men who had Just been led away thus were saved.

'lzz al-Din al-Masri, born in 1937, resident of Yarmuk camp

When we were being sheltered in Fraydiss, they let us return to Tantura to get clothing and blankets. My mother asked me to bring everything I could carry, especially her sewing machine, as well as a few pieces of gold hidden in the mattress. When I entered our house, I saw all our things in big piles in the middle of each room But there was no sewing machine or gold pieces or jewelry of my mother and sister.Along the railroad tracks between Tantura and Fraydiss, I saw the bodies of Sulayman al-Masri and his son Ahmad. Later, when we were gathered in a school in Tulkam, waiting to set off towards Hebron, Israeli planes came and shelled us. Two children from Tantura were killed, the son and daughter of Yahya ai-' Ashmawi.

Wurud Sa'id Salam, born in 1937, resident of Yarmuk camp

It was Saturday night, and we were sleeping when the battle began. We immediately got up and my mother called on God for protection. My father was a member of the Resistance. We hurried to a house where a lot of people had gathered. Then soldiers arrived and ordered us out. We walked along the Marah. My mother suddenly started to scream: she had recognized the body of my uncle, Fadl Abu Hana. A Jew aimed his gun at her and threatened to kill her if she didn't shut up.

Leaving our house, we took a few things with us for fear that the Jews would steal them--a gold pen, a ring with the name of my father engraved on it, some earrings and 8 Palestinian pounds. When we got to the beach, my mother buried them in the sand, marking the hiding place. Later, at Fraydiss, a colonist from Zichron Yaacov who had a restaurant that my father supplied with fish recognized us. My mother told him where she had hidden our valuables, and he brought them to us. Nothing was missing. I remember that his name was Lolik.

To come back to the massacre, when we were passing the cemetery, my mother said: "There's the body of Salman al-Shaykh!" In my panic, I had almost stepped on his body but my mother held me back by my clothing. It was also near the cemetery that we saw my father carrying the body of Hajj Abd al-Dassuki, but he didn't go very fur and laid the body down among the prickly pears for fear of being shot himself: He was wounded.

Near the low wall of Umm Fakhriyya, we saw twelve bodies, all from the Abu Safiyya family.

After we were handed over to the Red Cross at Tulkarm, we had to set off again. We were barefooted. The asphalt was burning hot and we were hopping about like sparrows.

No comments:

Post a Comment