Algeria, Palestine, and the limits of humanism

Albert Camus rejected Algerian independence and anticolonial violence in favor of a vision of bourgeois humanism. Palestinians are now encountering similar sentiments, reminding us that humanism is often the privilege of those already living in humane conditions.

It was 66 years ago that, amidst a raging war, the French-Algerian writer Albert Camus gave his most perilous political speech: outwardly, his speech was a call for a civil truce in Algeria; inwardly, the decline of Arab nationalist aspirations, and in its aspirations, a humanist avowal of shared possibilities on land shared between colonizers and the colonized. Amidst public pleas for decolonial violence, Camus — one of the Pieds-Noirs — presented himself as a person outside the dichotomy of the colonizer and the colonized, a mediator, above all, who despised indiscriminate violence and sought dialogue among the French and the Arabs of Algeria.

As demands for a ceasefire in Gaza gain global political momentum, I think it is worth critically exploring Albert Camus’s thoughts on French colonial history in Algeria for parallels and breaking points with the present moment. Drawing on those parallels, this leads to the conclusion that resisting oppression through violence is sometimes the only means available to the oppressed — importantly, for Camus, this is not a justification for violence but a realistic assessment of the effects of oppression on the oppressed.

When Palestine is calling on resistance, we owe it some difficult questions about the legitimacy of self-defense, the limits of violent resistance, and the accountability of the original oppressor. Albert Camus, I think, can help us find some answers.

It goes without saying that the historical context of Algeria cannot be paralleled entirely with the Palestinian situation. But where the Algerians and the Palestinians share a common fate is in being the recipient of systematic oppression. It is this parallel alone that guides the following reflection.

French colonization of Algeria: a brief history

France’s oppression of the Arab Algerians took place in phases.

The first was a conquest that lasted from 1830 until 1870. Through military action, France committed mass atrocities on a large scale, obliterating entire villages, violating their inhabitants, and seizing their cattle and their crops.

During the second phase in 1870, civilian settlers from the metropole slowly took over Algerian land. The settlements were ruled by French laws known as the “Indigenous Legal Code,” a racist piece of jurisdiction that deprived Algerians of all protections against the rights afforded to the European settlers.

The third phase unfolded after 1870 when the settlers faced erratic insurgencies. In response to violent outbursts, some French called for a reformist approach that would afford limited rights to a limited number of Algerians (those deemed “civilizable”). The real objective behind those reformist attempts was to separate the Algerian masses from the Algerian political leaders, and thus to fracture mass support for Algerian political autonomy. Notably, the FLN challenged France’s division policies directly at the “Battle of Phillipville.” The FLN deliberately caused civilian deaths to separate the Algerians from the French. The battle is now widely creditedas the first victory of the armed insurrection.

This brief history of Algerian colonization should sound familiar to anyone aware of key points in Palestinian history: The mass expulsions in ‘48, the ‘67 war, the First Intifada, the reformist Oslo Accords, the outbursts of violence during the Second Intifada, the subsequent scattering of Palestinian political representation, the withdrawal from Gaza, the Unity Uprising, and so on.

As a young man, and throughout his life, Albert Camus favored the reformist approach of the French progressives. In 1936, he embraced the Blum-Viollette bill, named after the leader of the French Popular Front, Léon Blum, and the French governor-general of Algeria, Maurice Violette. The Blum-Viollette agreement — the Sykes-Picot of French Algeria, as it were — would have granted some rights to a tiny minority of Algerians. Note how not a single Algerian was seated at the negotiating table.

At 23 years old, Camus co-authored a manifesto that supported the reform plans:

“Granting more rights to the Algerian elites would mean enlisting them on [the French] side […] far from harming the interests of France, this project serves them in the most up-to-date way, in that it will make the Arab people see the face of humanity that France must wear.”

The Oslo Accords, a much-scolded concession by the Palestinian Liberation Organization, were welcomed, and justified, in a similar way: the accords would force a face of humanity on the occupation, show to the world the moral righteousness of Israel, and display Palestinians’ “reasonableness” and political “goodwill,” Edward Said famously demurred.

By the end of the Second World War, the repression of Algerians was ruthless and was followed by a decade of massacres. Thousands of Arab civilians were killed by the French army, air force, police, and settler militias. Within less than a decade, France dropped 41 tons of explosives on insurgent areas. These days, Israel has thoroughly surpassed this sad record. These events in Algeria were, and still are, severely underreported. Even by conservative estimates, reports convey the loss of about 10,000 Algerian lives.

The collective trauma inflicted on Algeria cemented the conviction among Algerian nationalists that national independence from France was the only way forward — self-liberation, by whatever means necessary. This decision was followed by a drawn-out war of independence.

Albert Camus, meanwhile, was accused of double standards. When Camus spoke publicly of “massacres,” he was referring to the occasional death of French civilian settlers. In contrast, when Camus spoke of “repression,” he was referring to the systematic killing of more than ten thousand Algerian civilians by the French army, the French police, and settler militias. This should remind us of the narratives surrounding Gaza, pitching terrorism charges on the one side and calls for national self-liberation on the other.

Humanistic colonialism

It should now be clear — Camus was not a staunch anti-colonialist. Camus’s battle was one of common sense, reasonableness, and humanistic commitments. “It Is Justice That Will Save Algeria from Hatred,” he titled one of his post-war essays. But for justice to manifest, he explained, France had to undertake a “second conquest” — a conquest, this time, escorted by diplomatic niceties.

In 1958, Camus finally unraveled. In his infamous speech in Algiers, he eventually made clear to his Algerian audience that his long-standing political work equaled a rejection of Algerian national independence. He dismissed self-liberation as a “purely emotional expression” in sharp contrast to the cold, dispassionate rigors of real politics. In words that must remind us of the enduring Palestinian condition, Camus spoke:

“Reason clearly shows that on this point, at least, French and Arab solidarity is inevitable, in death as in life, in destruction as in hope. The frightful aspect of that solidarity is apparent in the infernal dialectic that whatever kills one side kills the other too, each blaming the other and justifying his violence by the opponent’s violence. The eternal question as to who was first responsible loses.”

In this violent climate, Camus traveled to Algiers, anticipating widespread support for his humanitarian appeals. For him, Algerian national independence simply was not one of the available options. Too strong, he thought, were the ties between the colonizers and the colonized.

Camus’s solution was a sort of republicanism — equal political rights in both Paris and Algiers. In other words, Algeria was meant to remain a part of France, but France had to bestow it with the systematic and sincere application of the rights, duties, and benefits of citizenship. If France failed to do so, he cautioned, it would “reap hatred like all vanquishers who prove themselves incapable of moving beyond victory.” Keep calling for national independence, he warned the Algerian Liberation Front (FLN), and perpetual war and misery would befall the Algerian Arabs.

At the Cercle de Progrès, Camus’s speech expressed how he believed that both sides were right; the problem, tragically, was that each side claimed sole possession of the truth. The audience responded with murmurs of outrage, and soon stones began to fly. When he suggested that “an exchange of views is still possible,” he was silenced by the angry audience. The FLN countered with passionately nationalistic speeches.

Camus failed in his noble goal of saving the lives of countless civilians, Arabs and French alike. Likewise, the current calls for a ceasefire in Gaza will likely yield the same sad results. The slaughter of civilians continued for another six years until France “granted” independence to Algeria. Rather than decolonization by “consent,” political commentators and historians now agree that Algeria has been decolonized by the force of the colonized.

To the French in Paris, Camus embodied the lowbrow philosophical position, a politically naïve mouthpiece of the Arabs; to the Arabs in Algiers, his Parisian aloofness and insistence on transcending the morality of both the colonizers and the colonized were easily identifiable as the common pathology of the white man.

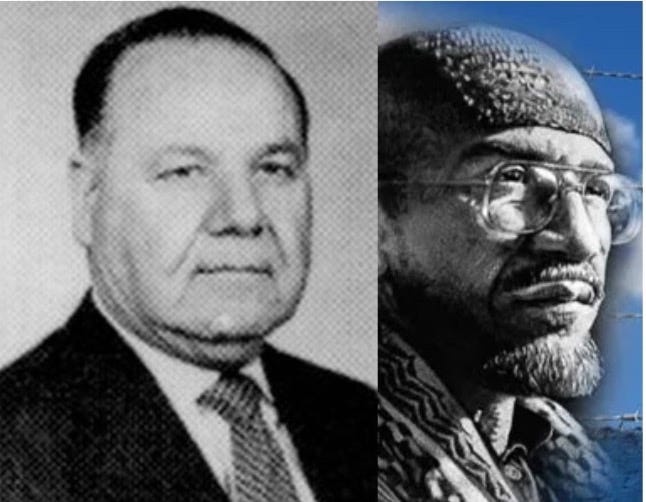

After the events in Algiers, Camus felt hopeless about the situation in Algeria. He stopped speaking publicly, withdrew into writing prose, and slowly realized that his humanistic goodwill was thoroughly misplaced. Only later would he carefully contextualize his absence from the cause, opining in his philosophical manner how he surrendered his lucidity in the realization of the tragic character of the human condition — that there is no room for philosophical thought as violence rages on. This observation was beautifully translated into words by the Palestinian militant intellectual Basil al-Araj.

Albert Camus remained silent because he refused to give up his loyalty to both communities. But in this situation of pure violence, however, he had to recognize the futility of his political goals. He could not, after all, reconcile his humanism with the violent state of war.

After he received the Nobel Prize in Stockholm, an Algerian student questioned Camus about his anti-independence politics. Although he believed in justice, Camus said,

“I have always condemned terror. But I must also condemn terrorism that strikes blindly, for example, in the streets of Algiers, and which might strike my mother and family. I believe in justice, but I’ll defend my mother before justice.”

This implicitly recognized the injustice of the colonial system and the personal effects it had on Camus himself. He was not, after all, the aloof, dispassionate political observer hailing to the colony from the metropole to speak in the service of the “civilized people” of Paris. Both the colonial system and the national liberation movement, he thought, had done him an injustice — he, the French-Algerian, had strong ties with both the colonizers and the colonized. For that matter, he could not choose between them, and all he could do was condemn the violence on both sides. More importantly, Camus believed that any nationalistic ideal was secondary to the safety and well-being of those dearest to him.

Camus failed to recognize that the violence unleashed by systematic oppression is almost inevitably uncontrollable and beyond justification and reason. If we were to ask the FLN, however, I would think they would talk about violence as deliberate, calculated, and part of a strategy. It is only to the outside, to the observers, that violence looks indiscriminate and uncalculated. In a similar vein, Palestinians like Basil Al-Araj were trying to convince me that there is no room for political subtleties, philosophical deep-dives, and bourgeois humanism whenever violence strikes the strongest. Camus’s silence spoke eloquently to this realization, underscoring Basil’s implication that humanism is often the privilege of those already living in humane conditions.

I think I understand Camus’s position. And I think it can be applied to Palestine. The fear and force of violence, Camus noticed, is always stronger than reason and morality. He also recognized that competing nationalisms breed violence, never solutions.

Through encounters with Israelis and Palestinians, I learned to think of Israel and Palestine as a site of possibility — a place where the very idea of the nation-state, which has harmed both peoples, could be remade or destroyed entirely. And it was Palestinians and Israelis alike who opened my thinking to multiple visions of sharing this land.

Addressing visions for post-nationalism in his 2009 film, “The Time that Remains,” Elia Suleiman wants us to raise the Palestinian flag as a sign against oppression and hatred. But, he says, as soon as this oppression is overcome, with all the freedom and dignity it brings, we will have to take the flag down.

Before you go – we need your support

At Mondoweiss, we understand the power of telling Palestinian stories. For 17 years, we have pushed back when the mainstream media published lies or echoed politicians’ hateful rhetoric. Now, Palestinian voices are more important than ever.

Our traffic has increased ten times since October 7, and we need your help to cover our increased expenses.

No comments:

Post a Comment