Weird Things About King Charles' Coronation

As Symbols are Twisted, Is Britain Being De-Consecrated?

As I watched King Charles III’s coronation, I had a creeping sense — as perhaps many did — of what Dr Sigmund Freud called, in a paper by that name, “Das Unheimliche” — or the “uncanny”. [https://www.sas.upenn.edu/~cavitch/pdf-library/Freud_Uncanny.pdf ] That is the sense of unease one has when something strange is located in the familiar; when there are subliminally disturbing inversions, doublings, or reversals; and when unease is stirred by one’s subconscious becoming aware of ordinary reality going awry.

A Polish expert on AI once gave a lecture at AIER that offered an example of the “uncanny” in ordinary modern life: she described an experiment which found that students could deal just fine with AI texts from a virtual concierge, and even with an AI “voice” assigned to it, but that they were made extremely uncomfortable by an AI-generated “human face” as an add-on.

Did you feel a bit uneasy when you watched the Coronation of King Charles III, on May 6, 2023? If so, perhaps you don’t even know consciously why that might be. King Charles’ coronation was shot through, in my humble opinion, with moments and examples of “the uncanny.”

Ritual — especially national ritual, especially at momentous symbolic occasions such as births and burials, inaugurations, investitures, and transitions of power — gains its human potency by being predictable, and, to some extent, by being repetitive. When one sees an English monarch holding a scepter and an orb — and you know that that iconography: “Scepter/Orb” extends back for centuries, in English literature, history, art and public spectacle — one has a sense of nationality, of course, but also of stability and continuity.

The same is true for other countries. When we as Americans see the Stars and Stripes saluted - and we know that it is the same salute that goes back most of our nation’s history - we are comforted. When the US President ends his every major speech with the phrase “and God Bless the United States of America”, that repetition is not only reassuring, it creates an invocation for our national life extending from deep into the past, giving us promise for the future.

All of this is a form of positive magic.

Britain has long been seen by other countries as being a bastion of reverence for its own national traditions. Indeed, other countries envy Britain the stability it achieved in the past by its respect for the ancient lineage of its traditions. Whatever you may think of the British monarchy, it has been a remarkable accomplishment for a single nation to so burnish its symbols and traditions, and to so maintain its national life and identity, that it could punch so far above its weight, as they say, for so long. It is remarkable that this tiny island could produce a glorious literature spanning centuries, innovate freedoms of speech that affected everyone, break boundaries in terms of technical and industrial progress, dominate the entire globe for a time, and, in the past century, help to overcome global fascism.

Britain’s reverence for its own mythologies, language, religion and rituals is not the only reason for this remarkable historical record. But it has surely helped.

This chain of continuity is partly what accounts for the richness of English literature; eighteenth-century scenes of courtship in Springtime yield to 19th century revisions; eighteenth-century aristocratic pretensions in Palladian houses are gently mocked in the early 19th century, updated to red-brick manor houses, and all this is updated to be mocked again in the early 20th, though set this time in speakeasies. The anticipation of a Shakespearean wedding is echoed by the anticipation of a wedding in Jane Austen, and fast forward to Nancy Mitford. The eras, the symbols, speak to one another.

The English monarchy, of course, though it has changed over the centuries, also jealously guards its longstanding symbolism, its solemn ritual; with all of this bolstering, of course, its claim to Divine Right to rule.

That is to say, this all was the case — until King Charles was crowned last week.

I do not know why some aspects of King Charles’ coronation were so weird, and deviated so notably from the “baseline,” or norms, of other English coronations. I just know that they were.

First there were the odd discordancies.

There were the black horses ostensibly in formation — yet at times dramatically out of step; the soldiers in black busbies with their alignments of arms and legs directly out of rhythm with one another; a lonely redcoat walking in the opposite direction of everyone else (see below), a red-coated soldier collapsing (which seems to happen regularly now at these events, [https://www.gbnews.com/watch/soldier-coronation-uk-military-royal], and other unnerving deviations from traditional display of discipline, order and symmetry.

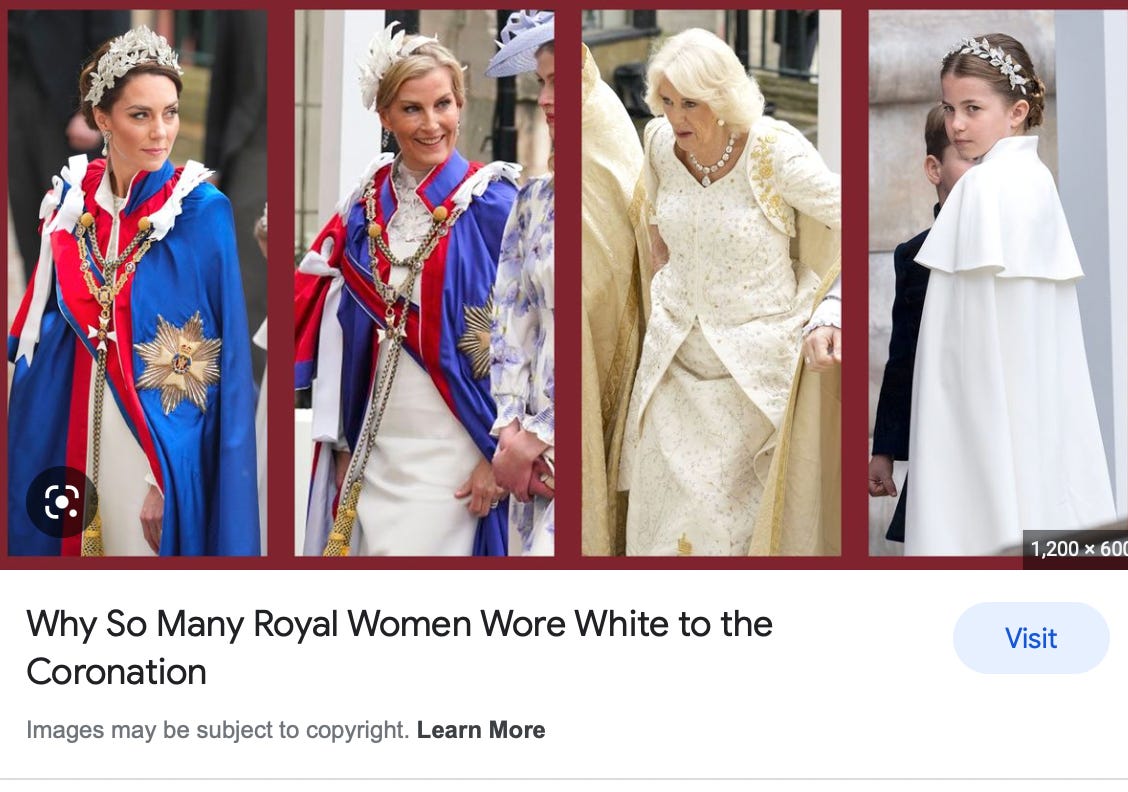

But leaving those aberrations aside — why were a number of key female attendees, in shapeless, Druid-like, white gowns?

This is entirely aberrant.

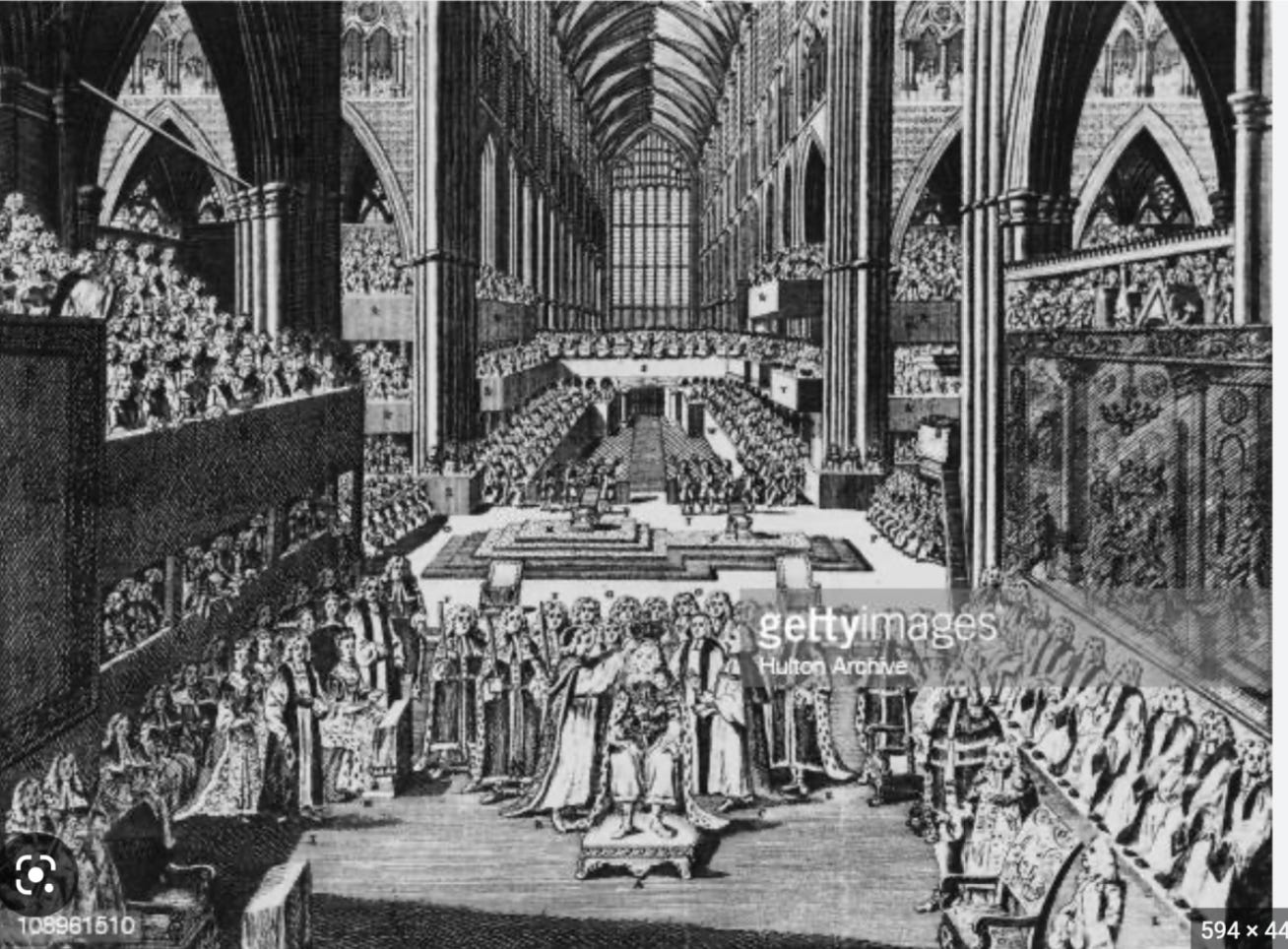

Past coronations certainly put the significant female attendees in white gowns. But they were the white dresses of that sartorial moment. The headdresses that female royalty wore, were traditionally tiaras. Here is Queen Elizabeth and the ladies of the Coronation. The year was 1953, and the cut and style of the gowns are normal formal dress for wealthy women in that period (of course the sashes of rank, and tiaras, are specific to the occasion):

Below is the coronation of George V and Queen Mary, 1911: the Queen is wearing a gown typical of the fashions of that year.

Now let’s go to 1838, when the young Queen Victoria was crowned; the ladies attending, again, wore the dresses and hairstyles characteristic of the fashions of that year:

This is the coronation of King George III, 1761: once more — the ladies are dressed in the gowns and hairstyles of the style of that year:

We could go on and on. In past coronations, ladies wore clothes and hairdressings typical of their time and social station.

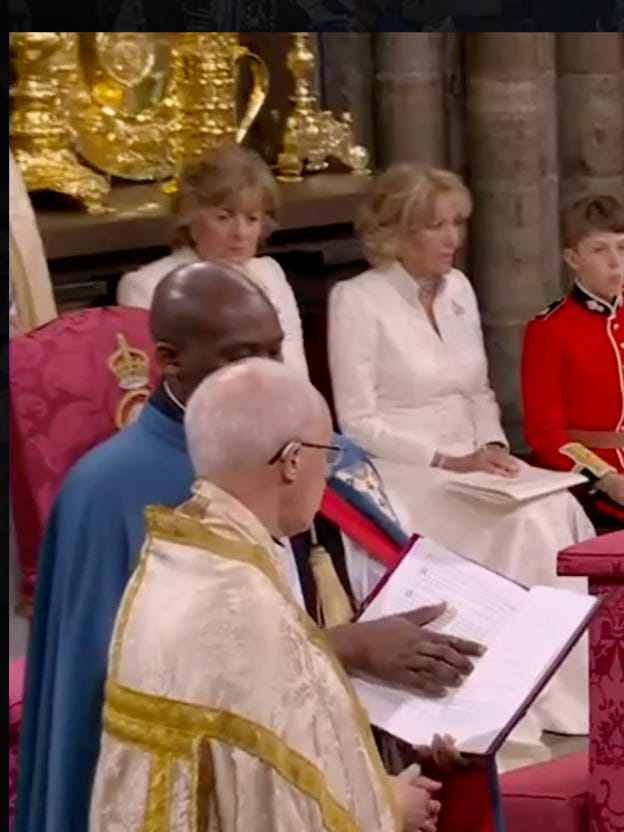

But at King Charles’ recent coronation, here is what key ladies wore: ankle-length, tunic-like, strangely similar, extremely unfashionable, Handmaids’ Tale-type long-sleeved white gowns:

The similar look of certain of the key royal-attending ladies, who all wore these awkward white gowns, and even of tiny Princess Charlotte, with the jeweled wreath on her hair, and the capelet, was notable:

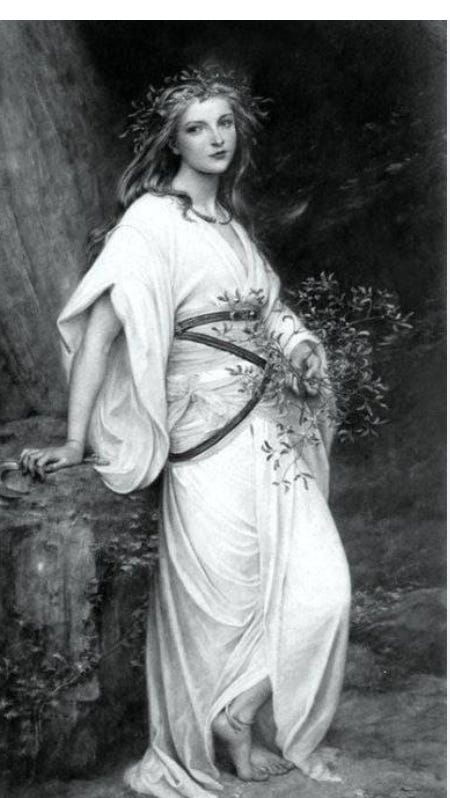

What was familiar about the scene?

If you look at images of Druidic gatherings, you will see women (and men) in long, loose white robes; you will see capes. You will see wreaths, like the kind that Princess Kate, Princess Sophia and Princess Charlotte wore, though in fresh leaves and flowers rather than in gemstones and feathers. Druidic Britain is a pre-Christian Britain, in which nature - groves, springs, rocks, trees — is worshipped, rather than Jesus Christ, or the Judeo-Christian God. This is a Druidic ceremony at Stonehenge, below. (Druidism has been a state-sanctioned religion formally in Britain since 2013.)

There are other bizarre moments and themes in the Coronation King Charles.

Weird is the introduction of an elaborate “privacy screen” behind which the anointing of the Monarch took place. Contemporary news accounts claim that this “screen” is like the canopy that King Charles’ mother, Queen Elizabeth, used in her own ceremony.

The anointing of the King or Queen has always been at the centerpiece of this solemn ritual. The holy oil consecrates the Monarch to the people and to God.

“The anointing is the most sacred part of the coronation ceremony, and takes place before the investiture and crowning. The Archbishop pours holy oil from the Ampulla (or vessel) into the spoon, and anoints the sovereign on the hands, breast and head. The tradition goes back to the Old Testament which describes the anointing of Solomon by Zadok the Priest and Nathan the Prophet. Anointing was one of the medieval holy sacraments and it emphasised the spiritual status of the sovereign. Until the seventeenth century the sovereign was considered to be appointed directly by God and this was confirmed by the ceremony of anointing. Although the monarch is no longer considered divine in the same way, the ceremony of Coronation also confirms the monarch as the Supreme Governor of the Church of England.”[https://www.rct.uk/collection/31733/the-coronation-spoon#/:~:text=The%20anointing%20is%20the%20most,the%20hands,%20breast%20and%20head.]

Here is a video (similar ones are not easy to locate online) that reaches to the point of Queen Elizabeth’s anointing. We can hear the invocation clearly as she is anointed — head, hands and breast. While we do not see the anointing, which may indeed have been covered by a golden canopy, we hear it clearly; she does not appear to leave the presence of the assembled crowd. She is asked to defend God and the Church; the anointing is described in real time; the word “God” is audibly invoked multiple times.

in contrast, the anointing is drowned out as well as unseen, in king Charles’ coronation.

King Charles in contrast requested an elaborate, embroidered, three-sided “privacy screen” and the event itself is now far more obscured.

In a process that to my knowledge has never happened before, the “Anointing Screen” was produced in separate sections in Westminster Abbey, and assembled at the altar; it shielded the Monarch from view, like a portable shower at the beach, for the sacred mystery of the act of anointing. It also enclosed the words invoked over the Monarch.

One problem with the “Anointing Screen” is its obscurity. This moment now is not audible, and thus far less transparent to the nation, than was the same moment when King Charles’ mother underwent the same consecration.

[https://www.royal.uk/news-and-activity/2023-04-29/the-anointing-screen]

Indeed, the lovely sound of the choir singing Handel’s “Zadok the Priest” entirely drowns out the words of this recent anointing:

This may seem like an extreme concern to raise — but is any concern extreme these days? If British subjects cannot hear their King’s Anointing — it is literally drowned out, starting at two minutes in, in the clip above, by the robust choir — how do they know what has been said? It could be anything — or nothing. In the United States, we are hearing rumors now that members of the Biden administration may not have taken the Oath of Office: “I […] do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same […] So help me God.” [https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/5/3331]

If that were ever to be the case, this would be a big deal. These officials would have legal leeway to do much of what they want — including commit what would otherwise be treason. If King Charles’ subjects cannot hear the Anointing, how do they know to what — to whom - he has consecrated himself?

How do they know if it is to the service of their God, or of themselves?

The “Anointing Screen” itself is weird. It has elements of the Ark of the Covenant as described in Exodus 25:10: it has poles of wood, to carry it, and cherubs at either end, facing each other:

“18 You shall make two cherubim of gold; make them of hammered work [m]at the two ends of the atoning cover. 19 Make one cherub [n]at one end and one cherub [o]at the other end; you shall make the cherubim of one piece[p]with the atoning cover at its two ends. 20 And the cherubim shall have their wings spread upward, covering the atoning cover with their wings and [q]facing one another; the faces of the cherubim are to be turned toward the atoning cover. 2” [https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Exodus%2025%3A10-22&version=NASB]

But there is an addition to this iconography, which causes that subliminal sense of the uncanny. Cherubim make a first appearance in the Hebrew Bible, holding flaming swords to protect the Tree of Life from mortal sinfulness, after Adam and Eve’s first sin, when they were exiled from the Garden of Eden.

These cherubs, in contrast (and a great deal was made in the British and global media about the design and execution of this hand-embroidered screen), face the Tree of Life cheerfully. There is no prohibition here, no defense of the Divine against mortal sin. [https://www.yahoo.com/lifestyle/why-anointing-king-charles-kept-122520176.html]

Weird too is the mere fact that an echo of the Ark of the Covenant was even created and brought to the altar of Westminster Abbey, which is one of the most sacred sites of the Church of England. The King of England is not a secular king. He is also the head, as noted above, of the Church of England. Unlike in America, and unlike in other secular nations, there is a state religion in Britain; and the Church of England, for which the nation was torn apart and countless reformers and clergy on both ‘sides’ of the conflict were martyred, is it.

But the Ark of the Covenant is also a pre-Christian (Jewish) sacred symbol. In Christian iconography, Jesus’ sacrifice did away with the need for a physical tabernacle. Christian iconography maintains that since Jesus brought God’s presence and the Holy Spirit to anyone, there is no longer a physical need for a Holy of Holies.

Christians also maintain (Matthew 27:51) that at Jesus’ crucifixion, the veil of the Temple (which in former times had housed the Ark of the Covenant, and was then the seat of the Holy of Holies) was torn in two; this also symbolized the division between the old order, in which a physical Temple was needed, and the new order, in which the Divine presence was always available to anyone. [https://www.progress-index.com/story/lifestyle/faith/2009/11/28/pastor-explains-significance-veil-being/985994007/#:~:text=Answer%3A%20The%20veil%20was%20the,%2C%20and%20the%20rocks%20rent.%22]

Given the bloody history in England of conflict between the Church of Rome and the Church of England, the Catholicism that King Charles has also included at the very center of his coronation, is a striking departure: Pope Francis gifted a relic of the True Cross. This gift from the Pope, startlingly to some of those who consider Britain’s painful religious history — the nation broke from the Church of Rome under King Henry VIII, in 1534 — proceededd into the Abbey ahead of the new leader of the Church of England. [https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/254135/pope-francis-sent-a-relic-of-the-true-cross-for-king-charles-coronation]:

So again, with the Druidic symbolism of all these loose white robes and crowns of leaves, and with the echo of the Hebrew Tabernacle, and with the omnipresent visibility in Westminster Abbey of Catholic officials and imagery, King Charles is diluting his nearly 500-year-old heritage as being the consecrated Governor of the Church of England, and he is departing from the history of his own nation by invoking symbols of pre-Christian (Jewish), or non-Christian (pagan), or non-C of E (Roman Catholic), times.

Even the motto that King Charles chose is — slightly off. He has chosen a famous quote from the mystic (again, the Catholic mystic) Julian of Norwich — which is embroidered, on a scroll that looks a bit like — a snake, at the foot of what I call the “Anointing Screen”’s Tree of Life (though it is called by Royal.uk, a “Tree of Commonwealth”).

But the quote is wrong.

The Royal.uk website, the official site of the monarchy, states: “Also forming part of the Commonwealth tree are The King’s Cypher, decorative roses, angels and a scroll, which features the quote from Julian of Norwich (c. 1343-1416): ‘All shall be well and all manner of thing shall be well’.” [https://www.royal.uk/news-and-activity/2023-04-29/the-anointing-screen]

But that is not the quote.

This is Julian of Norwich, describing her vision of Jesus:

“In my folly, before this time I often wondered why, by the great foreseeing wisdom of God, the onset of sin was not prevented: for then, I thought, all should have been well. This impulse [of thought] was much to be avoided, but nevertheless I mourned and sorrowed because of it, without reason and discretion.

“But Jesus, who in this vision informed me of all that is needed by me, answered with these words and said: ‘It was necessary that there should be sin; but all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.'

“These words were said most tenderly, showing no manner of blame to me nor to any who shall be saved.”’ [https://christianhistoryinstitute.org/incontext/article/julian/]

It may seem trivial to note that one “All shall be well” out of two, was deleted or elided from the full, accurate quote that was embroidered on the “Anointing Screen.” But Royal.uk is misinforming the public. The words the site mis-quote are not Julian of Norwich’s words.

They are the words of Jesus Christ, according to Julian of Norwich. So the King’s quote misquotes — according to the author — Jesus.

Also, the repetition of “All shall be well, and all shall be well” is incredibly well-known to students of English literature and history. It is an iconic phrase.

I have noticed that icons, symbols and texts that are culturally central to Western countries, and that are central to the Judeo-Christian tradition especially, are being slightly rearranged, slightly soiled, slightly garbled these days everywhere (just as President Biden keeps systematically not concluding his speeches with: “And God bless the United States of America”).

So by the King’s choice of motto slightly scrambling this culturally sacred, very famous English text — it is as if a US President were to slightly mis-print or mis-quote the opening lines of the Declaration of Independence, at his own Inaugural.

Then there is this image, above. Entirely tempering or countering his role as head of the Church of England, at the climax of the Coronation, a half dozen representatives of other faiths surround him. The Greek Orthodox priest, the Roman Catholic priest — the Rabbi? And others, all stand, while King Charles is seated. They do not appear as subjects, in a tableau of inclusion, which would be less odd. Rather they surround King Charles from positions of dominance — in a faintly intimidating display of participation in this ritual, or even of religious assertiveness.

I like inclusion as much as the next person, but this is not the Church of England officiating to consecrate the new Governor of the Church of England in one of the holiest sites for the Church of England.

This is something — else.

There are other phrases that are new, or wrong. There is no such thing, I will wager, as a “rod of equity and mercy” because that word “equity” is novel in the sense in which it is meant here; “equity” has only had the meaning that WEF types imposed upon it, since just a few years ago.

I won’t even go deeply into the weirdness of the balcony scene, which took place after the coronation was all over. Why are these preadolescent boys arranged in this cadre in this way? The nominal explanation is that they are members of the extended family, or “pages.”

But the iconography of this moment in the past did not, to my knowledge, include an aggregation, a lineup, of eight or ten 10-13-year-old boys. The balcony iconography is always the immediate and extended family, of all ages. What is this Lost Boys imagery? Why? (Are those indeed all boys?)

I have no idea what caused this odd aggregation of abstracted children, but it is a departure from tradition. And this deviation from tradition aligns with other tradition-, family-, and even gender-blurring moments: Princess Anne dressed, for instance, in male clothing; and a female official dressed in the masculine garb of the past, carrying the train of a male official, also in ceremonial dress.

It may be that all of this tweaking of ancient formulae, and all of these reversals and inversions, will create a reign of peace, prosperity and freedom for the people of Britain. I hope so. I love that country — really, those countries — and am anguished at the damage to its liberty and to its very culture, that it has sustained since 2020.

But — what is Britain now? What is America, for that matter, if all of our language of culture, identity, faith and patriotism is tweaked, mashed-up and upended?

Is that not the trend everywhere in the West — for a reason?

Do we not need our good magic, our consecration to a God with whom we are familiar, with whom we have a history? Do we not need transparent, time-honored rituals of service to nation and people?

Do we not need to know whom we actually are?

If we do know who we are, and insist on taking pride in our history, faith and cultural identity, are we not impossible to overcome?

If we forget everything — forget entirely whom we are — is it not easy for adversaries to drive right over us in their armored vehicles — over our crowns, orbs, screens; and over our poems, flags, and all?

No comments:

Post a Comment