Must the Palestinian have an Oscar for the world to care when he’s attacked?

We can't accept the rules of recognition set by the very powers that dispossess us, especially the idea that our success is what makes us worthy of protection.

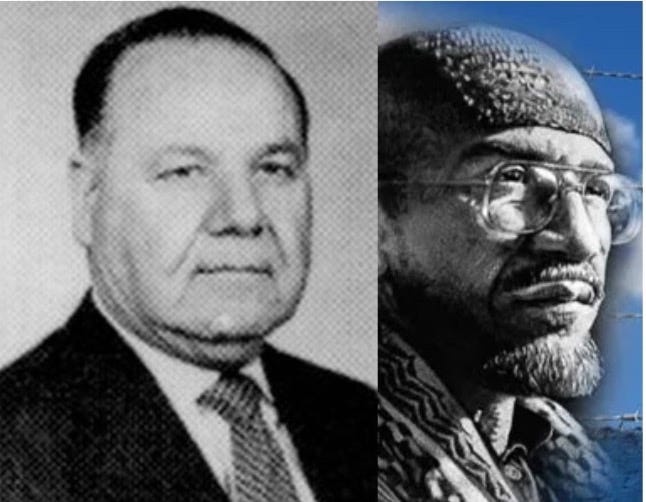

Last night, armed Israeli settlers descended upon the Palestinian village of Susiya in the Masafer Yatta region of the occupied West Bank and assaulted Hamdan Ballal, a contributor to +972 and co-director of the film “No Other Land” which recently won an Oscar for best documentary. Israeli soldiers were present at the scene and stood by as Ballal was attacked along with other residents and activists, only to then detain him and two other Palestinians overnight in a military base, where they endured further abuse.

When news broke of the settler ambush, the headlines focused almost exclusively on one thing: Ballal’s Oscar win. Across mainstream Western media — from the Associated Press and Reuters, to the Washington Post and the BBC — publications used surprisingly direct language to describe the attack on this “Palestinian Oscar winner.”

Unlike some of their coverage of Israel’s genocidal war in Gaza, for instance, these outlets clearly named the perpetrators of the assault — Israeli settlers — with one traditionally liberal publication going so far as to describe his brutal arrest by the Israeli army as a “kidnapping.” But still, the emphasis was clear: the assault and detention of a Palestinian is notable because he holds international acclaim.

Of course, what happened to Ballal is not random. As co-director of a film that documents the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians and the violent expansion of Israeli settlements in the villages of Masafer Yatta, he has used his platform to speak directly and unapologetically about Israeli apartheid and dispossession. Targeting him is part of a broader strategy of silencing Palestinian cultural figures and truth-tellers, especially those who succeed in disrupting dominant narratives on global stages.

But the framing of his assault and arrest should alarm us. Why must a Palestinian’s intellectual recognition be the basis for solidarity? Why does the global media insist on highlighting that Ballal is an Oscar-winning filmmaker?

This kind of solidarity, grounded in fame or intellectual achievement, dangerously aligns with colonial patterns of recognition. It reproduces the logic that some lives — those legible to Western audiences — are more grievable, more shocking to violate, and more worthy of defense.

Israeli and Palestinian protesters take part in a demonstration in Rabin Square against the government’s annexation plan, Tel Aviv, June 6, 2020. (Oren Ziv)

The underlying message is that if even an award-winning filmmaker isn’t immune to state violence, then something is truly wrong. But shouldn’t international media have recognized something was wrong when Palestinians without global awards — students, farmers, mothers, teachers, activists — are arrested by Israeli forces every day? Their stories rarely make headlines. Their names are rarely known.

A decolonial solidarity

The colonial logic reinforced by these headlines — that sees Palestinians as valuable only when they produce something recognizable or useful to Western audiences — has deep roots.

Under colonial regimes, the “good native” was always the one who spoke the colonizer’s language, produced art for foreign consumption, or performed civility in the approved ways. In Mandate Palestine, British authorities often favored dealing with urban, Western-educated elites in the cosmopolitan cities of Jerusalem and Haifa, those who could navigate colonial institutions and posed little threat to imperial control. At the same time, they violently suppressed rural resistance during the 1936–39 revolt, targeting peasants and nationalist organizers with collective punishment and military force. Today, Western recognition of the “good native” takes the form of awards for films, Ivy League fellowships, or inclusion in global humanitarian discourse.

To be clear: the problem isn’t that people are expressing solidarity with Ballal. It is that this solidarity is often conditional, selective, and deeply tied to notions of exceptionalism. It becomes easier to condemn injustice when the victim can be framed as brilliant, eloquent, or successful. It becomes harder, it seems, when the victim is one of the more than 9,000 Palestinians currently held in Israeli prisons — many without charge or trial, and whose names we will never learn.

These arrests are not incidental; rather they are central to Israel’s settler-colonial project. Detentionis a daily mechanism of control: of land, bodies, and futures. In Ballal’s case, the Israeli army accused him and others of throwing stones after settlers attacked them — an accusation so common it has become almost formulaic. Human rights organizations have long documented how stone-throwing charges are used to justify mass arrests and criminalize resistance, especially in the South Hebron Hills and across the West Bank.

Police arrest a Palestinian youth during a protest against a construction site for a new public park near Muslim graves, outside Jerusalem’s Old City, October 29, 2021. (Jamal Awad/Flash90)

What’s happening in Susiya is the same thing that’s happening across the entire land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea: a system of apartheid that views any form of Palestinian presence, whether political or artistic, as a threat. It is a system that uses military power not only to displace Palestinians physically but also to disrupt their ability to narrate their own reality. That Ballal used the global stage to tell this truth makes him a target. But the absence of an Oscar does not make the next person’s assault or arrest less violent, less strategic, or less political.

It might seem harmless, and indeed strategic, to point out that if even an Oscar winner is not safe, then no Palestinian is immune from Israeli settler and state violence — not the teenager walking to school, not the activist resisting demolition in Masafer Yatta, and certainly not the artist returning home after winning an international prize.

But when we do so, we inadvertently imply that others are less deserving of safety. We risk reproducing the very logic that justifies state violence: the division between the visible and the invisible, the grievable and the ungrievable, the exceptional and the disposable.

This is not a call to ignore the targeting of artists or intellectuals. On the contrary, it is a call to deepen our understanding of how Israeli violence operates, and to widen our scope of solidarity.

Solidarity with Palestinians must be decolonial. It must refuse to play by the rules of recognition set by the very powers that sustain our dispossession, including the idea that global success is what makes us human or worthy of protection. And it must hold space for all those who will never receive a headline — those whose homes are raided at night, whose children are detained for Facebook posts, whose resistance is quiet and ongoing and just as real.

Hamdan Ballal’s arrest is not shocking because he is famous. It is enraging because he is Palestinian — and because Israel continues, with impunity, to criminalize Palestinian existence.

No comments:

Post a Comment