WHO moves forward with plans to target “misinformation” and “disinformation” under international law

The global health agency claims that misinformation and disinformation undermined "compliance with governmental or WHO guidance."

The global unelected health agency, the World Health Organization (WHO) is marching forward with its plans to make amendments to the International Health Regulations (2005) which would give it new far-reaching powers to counter “misinformation and disinformation.”

The plans to amend the International Health Regulations (IHR) were set in motion in January last year when the Biden administration quietly proposed sweeping changes to the IHR.

Currently, the IHR are a legally binding instrument under international law. They require 196 countries to build capabilities to detect and report potential public health emergencies worldwide and respond swiftly to a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) whenever it’s declared by the WHO.

The amendments being pushed by the Biden administration sought to increase the WHO’s powers to declare “potential” health emergencies and empower the WHO to develop new global surveillance and data-sharing mechanisms.

But after the Biden administration sent its proposals, other member states submitted their own proposed amendments to the IHR. To date, 307 proposed amendments have been submitted. These proposed amendments go beyond the scope of the Biden administration’s original suggestions and seek to give the WHO additional powers to counter so-called misinformation and disinformation.

In a recent WHO meeting, that began on February 20 and ended on February 24, a working group of WHO representatives completed their reading of the proposed amendments to the IHR, agreed on the next steps for more in-depth negotiations, and planned for their next meeting which will begin on April 17 and end on April 20. A provisional timeline was also published that suggests the amendments will be finalized by May 2024.

We obtained a copy of the provisional timeline for you here.

How these proposed IHR amendments expand the WHO’s powers

1. New provisions that apply to “potential” health emergencies and health risks

The existing IHR allow the WHO Director-General to declare a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) which is currently defined as (link): “An extraordinary event which is determined to constitute a public health risk to other States through the international spread of disease and to potentially require a coordinated international response.”

They’re also restricted in their scope. Specifically, the purpose and scope of the current IHR is to “prevent, protect against, control and provide a public health response to the international spread of disease in ways that are commensurate with and restricted to public health risks.”

But these proposed amendments broaden the purview of the IHR by adding the word “potential” to several key sections. The amendments give the WHO Director-General the power to declare a “potential or actual” PHEIC and expand the scope of the IHR to include “all risks with a potential to impact public health.”

2. New powers to declare health emergencies

Currently, health emergencies can only be declared by the WHO Director-General and these declarations have to follow the PHEIC criteria. These proposed amendments allow the WHO to declare new types of health emergencies, give WHO Regional Directors powers to declare some types of health emergencies, and allow the WHO to issue new types of health alerts.

Specifically, the proposed amendments give the Director-General new powers to issue an “intermediate public health alert” to any country in response to events that don’t meet the PHEIC criteria, allow Regional Directors to declare a “public health emergency of regional concern” (PHERC), and allow Regional Directors to issue an “intermediate health alert.”

3. New provision recognizing the WHO as the “coordinating authority” during a PHEIC

Not only do these proposed amendments give the WHO new powers to declare health emergencies but they also recognize the WHO “as the guidance and coordinating authority of international public health response” during a PHEIC.

As part of this provision, all of the WHO’s member states agree to “follow WHO’s recommendations in their international public health response.”

The WHO’s plans to counter misinformation and disinformation under the IHR

The WHO already has significant influence when it comes to censoring online content that it deems to be misinformation or disinformation. It has partnerships with YouTube, Facebook, and Wikipedia. YouTube alone has censored more than 800,000 videos under a policy that prohibits going against the WHO.

But with these proposed amendments and the increased powers that they bring, the WHO is planning to further expand its influence in this area.

The proposed amendments direct the WHO to strengthen its capacities to “counter misinformation and disinformation” and build the capacities of member states to gain “leverage of communication channels to communicate the risk, countering misinformation and dis-information.”

Additionally, the proposed amendments empower the WHO to strengthen its capacity to “co-ordinate with “UN [United Nations] agencies, academia, non-state actors and representatives of society.”

We obtained a copy of the full list of proposed amendments to the IHR for you here.

We obtained an article-by-article compilation of the proposed amendments to the IHR for you here.

This push to grant an unelected global health agency new powers to counter misinformation and disinformation follows many people being accused of spreading misinformation and censored during the pandemic when they made truthful statements, such as stating that vaccinated people can spread Covid (a claim that authorities are now admitting is true).

Despite authorities now admitting that the vaccinated can spread Covid, the WHO has branded “vaccine hesitancy and the spread of misinformation” as hurdles that need to be tackled and even suggested that “anti-vaccine activism” is deadlier than “global terrorism.”

And in a report that it published alongside these proposed amendments to the IHR, the WHO continued to express its disdain for content that it deems to be misinformation or disinformation. The unelected global health agency claimed that misinformation and disinformation “hindered a meaningful public health response” during Covid and complained that it can “undermine public trust in health agencies and impede public confidence in, and compliance with, governmental or WHO guidance.”

The WHO also called for a “balance between ensuring more accurate scientific information on one hand and freedom of speech and the press on the other” in the report.

We obtained a copy of this report for you here.

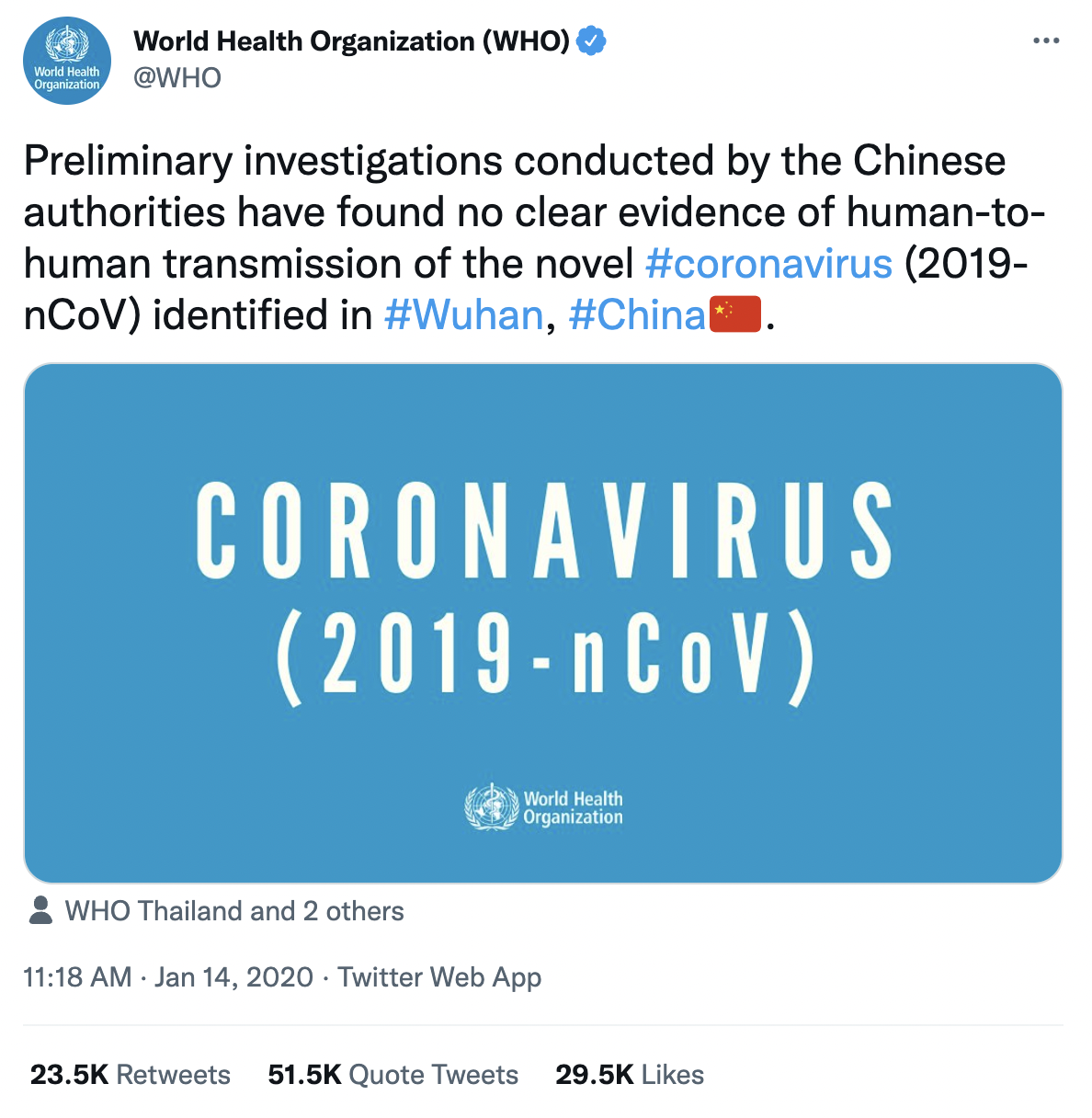

While the WHO has been very vocal about the purported harms of misinformation and disinformation as it creeps closer to getting new powers to target this content, the WHO itself pushed one of the most infamous pieces of misleading content during the early stage of the pandemic when it repeated China’s claims that it had found “no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission” of the coronavirus.”

Some politicians have opposed the proposed amendments to the IHR but this opposition has yet to prevent the WHO from moving forward with its provisional timeline of finalizing the amendments by May 2024.

The WHO has the authority to adopt these proposed amendments under Article 21 of the WHO Constitution. After the amendments are finalized, they’ll come into force for all member states “after due notice has been given of their adoption” by the World Health Assembly (WHA), the decision-making body of the WHO, unless member states reject them within a specified period. This specified period for these proposed amendments to the IHR is six months.

The WHO Constitution doesn’t specify how many votes are required to adopt amendments to regulations. However, according to SWP Berlin, a research institute that advises political decision-makers on foreign and security policy, WHO regulations require a lower voting threshold than conventions (which require a two-thirds majority vote).

Unlike the usual lawmaking process in democratic countries, where elected officials vote on the laws that apply to their citizens, most of the votes that determine whether a legally binding WHO convention or regulation applies to a country are cast by representatives from other countries. And many of the representatives casting these votes are unelected diplomats who can’t be voted out at the ballot box and often keep their position when the ruling party changes.

These proposed amendments to the IHR are just one of the pending changes that could give the WHO greater sway over online content. The WHO is currently negotiating the zero draft of its international pandemic treaty which targets misinformation and disinformation. Like with the IHR, the WHO intends to finalize the international pandemic treaty by May 2024.

And the WHO getting a potential increase in censorship powers is just one of the implications of these proposed amendments to the IHR and the international pandemic treaty being finalized. Both of these measures also push for increased surveillance powers and the proposed amendments to the IHR lay out a roadmap for international vaccine passports.