The Drowning Rats That Show Lockdowns Killed

Two Cruel Experiments With the Same Outcome

Born in 1894, Curt Richter was a significant figure in the field of psychology, known for his pioneering work in biological rhythms and behaviour. He spent much of his career at Johns Hopkins University where he conducted extensive research on circadian rhythms, the natural cycles that regulate various physiological processes in organisms.

In the 1950s he conducted a cruel experimenton rats, the results of which go someway to explain how lockdowns killed. Especially, the elderly in care homes, even without the sedatives and Do Not Resuscitate orders.

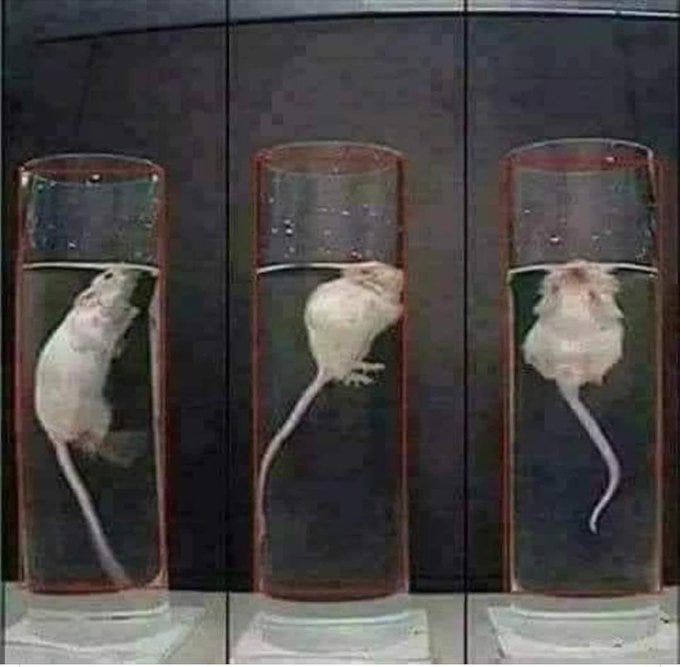

The purpose of the experiment was to try and understand the complex interplay between psychological states and physical endurance. To do so, he and his team placed individual rats in high-sided containers of water. This created a situation from which the rats could not escape and were forced to swim for their lives. They were unable to rest anywhere, therefore compelling continuous swimming, the intention to create an environment of inescapable stress. Even worse, a jet of water of any desired temperature was shot into the centre of the cylinder to prevent the rats from floating.

Richter also wanted to compare the differences between domesticated and wild rats in the experiment.

The average survival time for the domesticated rats ranged from 10-15 minutes at 63-73F to 60 hours at 95F, to 20 minutes at 105F. Strangely, at all temperatures, a small number of rats died within 5-10 minutes after immersion.

To try and eliminate these large variations in swimming times, Richter decided to shave the rats’ whiskers before the animals were placed in the water. They first started with twelve domesticated rats. Three of these rats dove to the bottom of their tanks, nosing their way along the glass wall before dying within 2 minutes of entering the water. However, the remaining rats swam for 40-60 hours.

They repeated the shaving experiment with hybrid rats (crosses between wild and domesticated rats) and five out of the six also died in a similarly brief time.

Finally, they experimented on recently trapped, wild rats. “These animals are characteristically fierce, aggressive and suspicious; they are constantly on the alert for any avenue of escape and react very strongly to any form of restraint in captivity”. All 34 died in 1-15 minutes after immersion in the jars.

Richter concluded that by trimming the rats’ whiskers, they had destroyed one of their most important means of contact with the outside world. For the wild rats, this was so disturbing that they gave up swimming almost immediately, devoid of any hope.

Humans are no different to wild animals. Remove someone’s means of contact with the outside world and they will lose all hope. They lose the will to keep on living, their minds and bodies weaken, before eventually succumbing to something they would have fought off if fighting fit and full of hope.

Lockdowns put the elderly into a metaphorical jar of water. They were trapped in their homes but still possessed the fighting spirit to survive. However, the killer blow came when they were denied access to friends and family. They were denied physical and social contact with other humans, removing their means of contact with the outside world. And like the wild rats, they simply gave up and stopped swimming.

However, the experiment didn’t stop there. Richter wanted to evaluate all possible causes of the prompt deaths of the wild rats and came up with 10 factors. He concluded that two of these factors were the most important. Firstly, the restraint involved in holding the wild rats, thus suddenly and finally abolishing all hope of escape. Secondly, the confinement in the glass jar, further eliminating all chance of escape at the same time threatening them with immediate drowning.

To me, lockdowns were identical. They were sudden and abolished all hope of escape. Not only that but the type of confinement meant these vulnerable humans realised there was no means of escape and the constant fear propaganda meant they felt threatened with immediate death.

“Some of the wild rats died simply while being held in the hand; some even died when put into the water directly from their living cages, without ever being held. The combination of both manoeuvres killed a far higher percentage. When in addition the whiskers were trimmed, all normal wild rats tested so far have died. The trimming of the whiskers thus proved to play a contributory, rather than an essential, role.”

Richter wanted to discover what actually caused the rats to die. He had assumed that the rats’ hearts would have accelerated due to exhaustion from swimming. However, after conducting EKGs, he noticed the opposite, the rats died from a slowing of the heart.

He discovered that pre-treatment with atropine prevented the prompt death of three out of 25 clipped wild rats. However, the domesticated rats, who had previously continued swimming for days, died within minutes when injected with sublethal amounts of drugs such as morphine.

“One tenth of the lethal dose of morphine sufficed to bring out the sudden death response in these rats, in effect eliminating this distinction between domesticated and wild rats.”

Richter had discovered that it wasn’t fight or flight that was causing the rats to die suddenly, it was hopelessness. He noticed that the rats literally just “gave up” and died.

Again, to ensure that his hypothesis was correct, Richter conducted a final experiment. This time he repeatedly held the rats briefly and then freed them, as well as immersing them in water for a few minutes on several occasions. “In this way the rats quickly learn that the situation is not actually hopeless; thereafter they again become aggressive, try to escape and show no signs of giving up. Wild rats so conditioned swim just as long as domesticated rats or longer”.

When the wild rats were given hope, they survived just as long as the domesticated rats. No longer did they despair. They had been trained to think there was light at the end of the tunnel and they wouldn’t give up until their bodies were fully exhausted. “After elimination of hopelessness, the rats do not die,” wrote Richter.

Richter conducted a cruel experiment that was repeated 70 years later in the form of lockdowns. Humans were trapped, subjugated to immense fear and stripped of any hope. Like the rats, they quickly gave up treading water in their isolated tanks and, full of despair, sank to the bottom. Don’t let any Covid inquiry convince you otherwise.

No comments:

Post a Comment