What Happens When There Aren’t Enough Jews to Lynch?

Ask the mob in Dagestan, Russia.

There are about eight hundred Jewish families left in the southern Russian republic of Dagestan. So the antisemites who live there have faced a supply-demand issue in recent days: a mob of salivating Jew-haters without sufficient Jews to lynch.

On October 28, the Flamingo Hotel in Khasavyurt, Dagestan, was stormed by a group of men looking for Jews. On October 29, the Jewish community center in Nalchik was set on fire—along with an inscription on one of its walls: “Death to the Jews.” In Cherkessk, on Russian Telegram, videos circulate of locals calling for Jews to leave the country.

So you can imagine the excitement when the people of Dagestan heard that a flight from Tel Aviv was landing on Sunday evening at the airport in the city of Makhachkala.

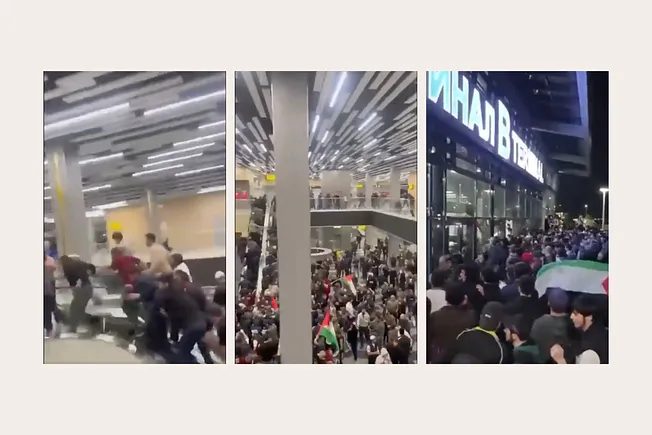

Hundreds of people stormed the airport to greet that flight—of 45 passengers, 15 were Israeli, many of them children. “Allahu Akbar,” they shout in videos that have emerged online, some men waving Palestinian flags. On the tarmac, they attack an airport employee, who desperately explains: “There are no passengers here anymore,” and then exclaims, “I am Muslim!” Some of the rioters demanded to examine the passports of arriving passengers, seemingly trying to identify those who were Israeli, and others searched cars as they were leaving. Another video emerged of two young boys at the airport, proudly declaring that they came to “kill Jews” with knives.

According to the local health ministry, more than 20 people were injured in the skirmishes. One video showed a pilot telling the passengers over the intercom to “please stay seated and don’t try to open the plane’s door. There is an angry mob outside.”

Today the Kremlin responded by blaming the airport attack on “external interference” from Ukraine and the West. Top Putin advisers were set to gather to discuss what they characterized as the “West’s attempts to use the events in the Middle East to split Russian society,” according to reports.

East of Georgia and south of Chechnya, Dagestan is one of Russia’s poorest regions. It is majority Muslim, and its most extreme religious strains have had a renaissance over the last two decades. The Kremlin has emphasized orthodoxy for all of Russia’s faiths, as Putin relies on religious leaders to be conduits for political support from the masses. (It was there, in the city of Makhachkala, that Boston Marathon bomber Tamerlan Tsarnaev reportedly became radicalized.) In the past year, Dagestan has been deeply affected by the war in Ukraine; official figures estimate that the region has had one of the highest casualty rates of the war.

After years of being gripped by Islamic insurgency, “Dagestani elites have been at pains to demonstrate their loyalty whenever possible,” Keith Gessen reported in The New Yorker last year—they are “deeply traumatized by loss, but. . . for the most part kept up a patriotic front.”

Scan the region’s Telegram channels, and Putin’s war on Ukraine barely exists. But the hatred of Jews, largely inspired by propaganda imported from abroad, runs rampant. In Utro Dagestan, a Telegram channel with 65,000 subscribers that called for the riot at the airport, messages encouraging the destruction of Zionists are constant. One post this morning read: “We initially asked not to make a pogrom. But since this is how it worked out, then we in any case support every person who was in the airport!!! [to protest] the crimes against humanity that the Jews are doing in Palestine.”

Few of these people, if any, could tell you that the Jews first came to Dagestan via Persia in the fifth century CE; the community has a tradition that they descended from the first exiles of Jews from Jerusalem. They traveled along the Silk Road and settled in the Caucasus in the early medieval period, speaking Juhuri, or Judeo-Tat, and are known as the Kavkazi Jews, or in Russian Gorskiye evreyi, which means “Mountain Jews.”

Today, there are an estimated 150,000 Gorskiy Jews worldwide—most of the community having migrated to Moscow, the United States, and Israel. Dagestan’s chief rabbi, Ovadia Isakov, estimates that there are as few as 300–400 families in Derbent, the republic’s oldest city, and the “same number throughout Dagestan.”

In the wake of the pogrom at the airport, a representative for Rabbi Isakov spoke with bewilderment on his behalf. “The situation is very difficult in Dagestan, people from the community are afraid, they call, but I don’t know what to advise,” he told a publication called Rise. “One woman turned to the local police officer for help, and he said: ‘Well, you see what you are doing to their children there.’ She tried to explain what Hamas was doing, but for the district police officer it was the opposite. The whole world is turned upside down for him and everyone else.”

Isakov himself had already narrowly escaped death at the hands of a local terrorist. In 2013, he was shot when returning from performing ritual slaughter for kosher meat. But he says today, “Is it worth leaving at all? For Russia is not salvation, there were pogroms in Russia too. It’s not clear where to run.”

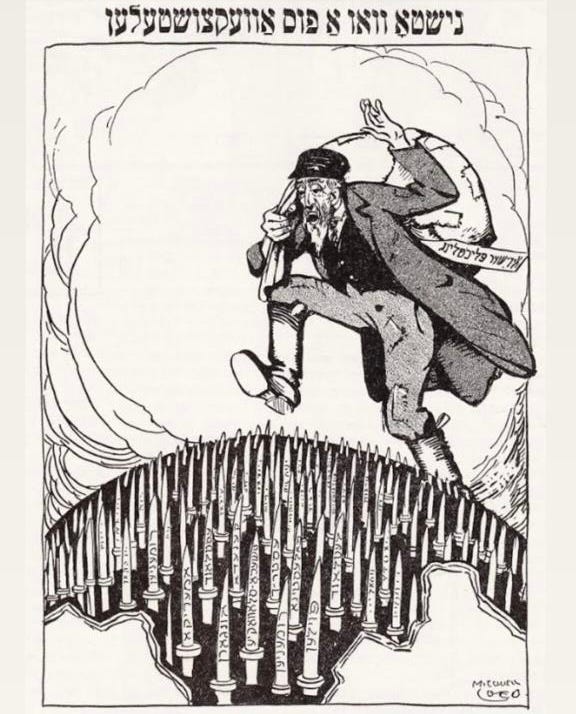

My family did run, back in 1979, from Soviet Ukraine and Russia. They ran to the United States, hoping for a life free from the pogroms that were the fate of so many of our ancestors, the all-too-familiar stories of murders and burning villages. We felt blessed to settle in New York. Children and grandchildren were born here who grew up feeling safe. Now we are shaken by antisemitic incidents on the rise around us, and by those flooding the streets cheering on the massacre of Jews. (This moment reminds me of an old Yiddish cartoon from 1921. It shows the wandering Jew, trying to put his foot down somewhere on the globe, but every country has daggers sticking out.)

But among many post-Soviet Jewish refugees, both family and community members, few are shocked by recent world events; their lives and memories have prepared them for this dark moment. “It is inevitable,” my grandparents tell me. They were evacuated out of Kyiv as toddlers, and so were saved from the fate of the remaining Jews—at least 34,000 of whom were slaughtered by the Germans in 1941 at a ravine called Babi Yar.

My father-in-law, Rabbi Pinchas Goldschmidt, was the chief rabbi of Moscow for the past three decades. But he, too, left last year, after refusing to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—which religious leaders are expected to do in modern Russia. He has repeatedly urged his community members to emigrate to Israel, where he now lives. He continues to do so, even with Israel under bombardment.

“When we look back over Russian history, whenever the political system was in danger you saw the government trying to redirect the anger and discontent of the masses toward the Jewish community,” he told The Guardian in December. “We’re seeing rising antisemitism while Russia is going back to a new kind of Soviet Union, and step by step the iron curtain is coming down again. This is why I believe the best option for Russian Jews is to leave.”

As for Dagestan, the reports in the paper would have you believe that the mob gathered in a kind of organic frenzy. But this is a country where nothing happens without state-level approval, whether proactive or passive. “The pogroms in Dagestan are taking place not only with the connivance, but with the coordination, of the authorities,” writes dissident journalist Dmitriy Glukhovskiy for Echo Moscow.

As Russian Jewish dissident and journalist Evgenia Albats tweeted: “Are there anti-Semites in Makhachkala? Yes, sure. Have there been before? Yes, sure. What happened now? 20 months of war, rising prices, hundreds, if not thousands of men killed, the pack is accumulating and requires a release.”

Note that the airport pogrom occurred three weeks after President Putin’s all-too-evenhanded comments on the Hamas massacre of October 7. It came after Russia’s U.N. Security Council resolution last week, which avoided mention of Hamas, and days after Moscow welcomed a delegation from Hamas, led by official Moussa Abu Marzouk. Marzouk insisted there would be no hostage exchange until Israel agrees to a cease-fire, and Hamas later thanked Putin for his “position regarding the ongoing Zionist aggression against our people.” This is not long after a Moscow-based crypto exchange, Garantex, transferred $93 million to Palestinian Islamic Jihad, which took part in the attacks on October 7.

Today, in the wake of the airport mob, Russian press Secretary Dmitry Peskov has wasted no time in redirecting the blame and declaringthat the airport attack was “Western meddling” intended to “divide Russia.”

But the Makhachkala airport scene was no backwater dream of a pogrom in some far-off republic. It is a whisper of something else, something far more sinister. That is, Russia’s attempt to direct its starved and war-devastated masses to blow off steam about the zhyd as in times of old. It is the oldest trick in the book: let them focus on the Jew, not on the falling ruble and the rising cost of food, not on the failing war that has ravaged their sons. It is the Jew that is the problem.

“Farewell, unwashed Russia / Land of slaves, land of masters,” the great Russian poet, Mikhail Lermontov, once wrote, imagining his freedom in the south of the country. “. . . Perhaps beyond the wall of the Caucasus, I will hide from your pashas / From their all-seeing eye / From their all-hearing ears.”

Alas, dear Lermontov, no one is safe from the reach of the Russian pashas.

Not even in Makhachkala.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt is a journalist whose work has appeared in the Atlantic, The New York Times, Foreign Policy, and The New Republic, among others. Follow her on Twitter (now X) @avitalrachel.

And to support more of our work, become a Free Press subscriber today:

No comments:

Post a Comment