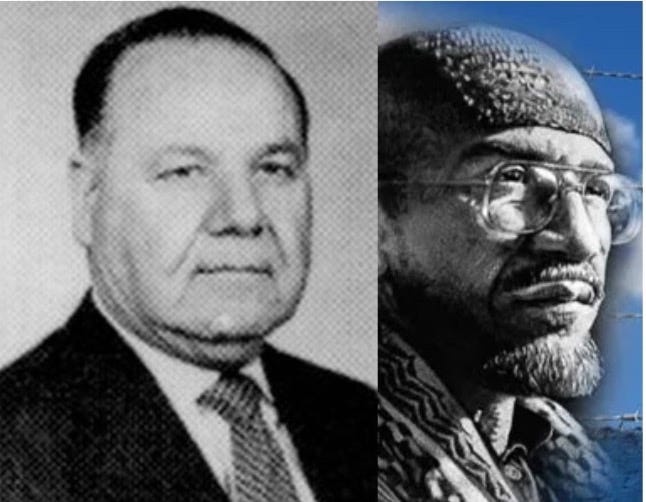

40 years after Jewish extremists murdered a Palestinian activist in California, no one has been held accountable

On October 11, 1985, Palestinian-American Alex Odeh was killed when a bomb destroyed his office. Despite suspicions that Jewish Defense League members carried out the attack, no charges have ever been filed. The unresolved case remains an open wound.

On Friday, October 11, 1985, Alex Odeh had breakfast with his wife and three young daughters, as he did every morning. It would be his last.

Alex headed to work at the western regional office of the American Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, a young civil rights organization based in Washington, D.C. The office in Santa Ana, a sprawling suburb in Orange County, was in one of the many ordinary buildings that lined E. 17thStreet. He parked in the back, took the stairs to the second floor, and turned down a long hallway. As he opened his office door, a bomb detonated, engulfing him in a fireball of shrapnel.

A nearby worker rushed toward the blast, through smoke and debris blocking his path. He later told reporters, “I looked down in the rubble and this guy was lying there and he was just bleeding.” He recalled shouting, “His leg is gone!” After placing his belt as a tourniquet on Alex’s torn leg, he helped evacuate onlookers, fearing another bomb might go off.

Alex died two hours later at nearby Western Medical Center. His family and friends were left stunned. Who would do this and why? They expected swift arrests and a trial to bring answers. Four decades later, no one has been charged.

Alex’s murder devastated his family. His widow, Norma, and their daughters grew up in the shadow of grief and fear. Norma took on the burdens of solo parenting, working multiple jobs to support the family. Alex’s siblings, Sami and Ellen, lived nearby, but passed away without seeing the case resolved.

Alex was a passionate advocate for Palestinian rights. In researching Alex’s life and views, one of the surprising things I realized was just how far his politics were far from being radical. His activism focused on improving Arab American representation in media and politics. He served on the local Human Rights Commission, supported electoral candidates, and regularly wrote to elected officials and news outlets. He believed traditional suit-and-tie civic engagement could open doors — an idea that now feels painfully quaint.

The blast that killed him reverberated across the Arab American community all the way to his birthplace, Jifna, in the West Bank near Ramallah. Alex was devoted to his hometown and helped organize the annual harvest of its famed apricots in the late spring. It must have been painful for him to be kept from going home. Israel denied his return because he was away from home, graduating from college in Cairo during the 1967 war, making Alex one of the Al Naksa generation. At first, he settled in Amman. Then he moved to the U.S., where his sister Ellen made her home. Such fragmented families, disjointed by events beyond their control, were common to Palestinians.

Investigators named suspects less than a month after the bombing. They were U.S.-born Israeli settlers with prior acts of violence against Palestinians. As everyone expected, they were members of the Jewish Defense League (JDL), which the FBI deemed a terrorist organization. The JDL was linked to a string of attacks going back more than 15 years, and were ritualistic in threatening Arab American activists, including Alex himself. Alex received calls to his work and home phones, requiring him to change numbers frequently. They ran mail to the office through a metal detector machine.

Soon after the bombing, the suspects returned to their West Bank settlement homes. A leaked FBI report documented displeasure by some investigators that Israel was not fully cooperating.

If Israel did start to assist, it was not self-evident. Two decades later, in 2006, U.S. Attorney General Alberto Gonzales told Israel’s Minister of Justice that the government’s “lack of response” over Odeh’s murder remained a concern for the FBI. We can speculate about the U.S. government’s commitment to solving the case. While local police and individual agents were committed to solving the case, it is likely that the higher-ups in Washington, D.C. were not. How could the government allow an ally to obstruct a murder investigation? Well, that’s the nature of U.S.-Israeli relations. It is built upon the adjoined pillars of impunity and complicity.

For Alex’s loved ones, the lack of closure remains an open wound. Arab-Americans of his generation see the case as proof of discrimination, believing the government failed to pursue the killers with full force. It is hard not to see this in the light of the genocide in Gaza: the unsolved case evinces a long-term American institutionalization of Palestinian dehumanization.

In the years after the bombing, the Arab American community contrasted the lack of progress in Alex’s case with President Ronald Reagan’s swift response to the Achille Lauro hijacking that same week. Palestinian militants took over the ship in the hope of securing the release of Palestinians Israel detained. After news broke that they killed an elderly Jewish-American man, Leon Klinghoffer, Reagan ordered fighter jets to intercept the plane carrying the hijackers following their negotiated end to the crisis. The American pilots forced it to land in Italy—an act that triggered a diplomatic standoff and led to the collapse of Italy’s ruling coalition. Reagan celebrated it by reading a statement that they sent a message to terrorists everywhere: they can run, but they can’t hide. Alex’s likely killers ran, but they had no need to hide.

Why, Alex’s friends asked, didn’t the U.S. take similarly dramatic action for Alex? The answer is, of course, that even for all his moderate politics, Alex was still Palestinian.

No comments:

Post a Comment