Multipolar World Order – Part 4

Iain Davis

Part 1 of this series looked at the various models of world order.

Part 2 examined how the shift towards the multipolar world order has been led by some surprising characters.

Part 3 explored the history of the idea of a world ordered as a “balance of power,” or multipolar system. Those who have advocated this model over the generations have consistently sought the same goal: global governance.

In Part 4 we will consider the theories underpinning the imminent multipolar order, the nature of Russia and China’s public-private oligarchies and the emergence of these two nations’ military power.

The Wider Context of the Ukraine War

There is no evidence to suggest that the war in Ukraine is, in any sense, “fake.” The political and cultural differences among the populace of Ukraine are older than the nation-state, and the current conflict is rooted in long-standing and very real tensions. People are suffering and dying, and they deserve the chance to live in peace.

Yet, beyond the specific factors that led to and have perpetuated the conflict in Ukraine, there is a wider context that also deserves discussion.

The so-called leaders in the West and in the East have had ample opportunity and power to bring both sides in the Donbas war to the negotiating table. Their attempts to broker ceasefires and to implement the various Minsk agreements over the years were weak and half-hearted. Both sides, it seems, chose instead to play politics with Ukrainian lives. And both sides ultimately fuelled the conflict.

The West has done little but exacerbate the situation. And, though it faced a tough economic choice, the Russian government could certainly have leveraged its commanding position in the European energy market to better effect.

If, that is, avoiding war were the objective.

Whatever else it is, the war in Ukraine is the fulcrum for a transition in the balance of geopolitic power. Like the pseudopandemic that immediately preceded it, the war is accelerating the polarity shift.

UK Defence Secretary Ben Wallace was right to observe that the Ukraine war is “a gift to NATO.” Just as the West has delivered the Russian government’s monetary policy to them, so Putin’s administration has rescued NATO from vanishing relevance. Both poles are strengthened, if for different reasons.

UK Defence Secretary Ben Wallace was right to observe that the Ukraine war is “a gift to NATO.” Just as the West has delivered the Russian government’s monetary policy to them, so Putin’s administration has rescued NATO from vanishing relevance. Both poles are strengthened, if for different reasons.

At the same time the European Union (EU) is capitalising on both the war and the sanctions it imposed in order to reinvigorate its push towards EU military unification.

The UK is involved in this push, even though in 2016 its population elected, via referendum, to leave the EU, specifically because a majority of voters did not want to give “national sovereignty” away to the union leadership.

But, as we can see, it doesn’t matter what the people vote for or against. Despite having supposedly left the EU, the UK’s newly unelected Prime Minister has just signed up the UK as a “Third State,” bound by Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) agreements, under the direct military command of Brussels. As the UK partly hands its independent defence capability to the EU, it is playing its part in assisting the emergence of another pole.

The International Monetary and Financial System (IMFS), which has thus far underwritten unipolar domination, is being transformed now that it’s reaching the end of its life cycle. Economic growth is being deliberately stifled in the West via sanctions but encouraged in the East. Energy flows and consumption patterns are being redirected eastward. Simultaneously, effective military power is being “rebalanced.”

During the pseudopandemic, we saw much evidence of global coordination. Most unusually, almost every government acted in lockstep. China, the US, Russia, Germany, Iran, the UK and many other nations followed the same false narrative. All participated in shutting down global supply chains and limiting world trade. Most countries assiduously heeded the World Economic Forum’s preferred path of global “regionalisation.” The few that resisted were considered international pariahs.

What has happened since then? We’re told the war in Ukraine has reintroduced the same old East-vs-West division that most of us are more familiar with. Yet in nearly every other significant way nations remain strangely in total agreement. It seems The war in Ukraine is practically the only dispute.

Multipolar Theory

The proposed multipolar world order does not constitute a defence of the nation-state. We have already discussed how the multipolar model dovetails quite precisely with the “Great Reset” (GR) agenda, so it should come as little surprise that multipolar theory also rejects the suggested Westphalian concept of national sovereignty.

Russia has numerous think tanks and GONGOs (government organized non-governmental organizations). Just as in the West, these are funded and influenced by both the public and private sectors, working in partnership. As noted by the Swedish Defense Research Agency, Russian think tank funding “part comes from the government and the rest from private actors and clients, usually big business.”

Katehon is the “independent” think tank established by Russian oligarch Konstantin Malofyev (Malofeev), who has been sanctioned by the US since 2014 for his support of Ukrainian Russians, first in Crimea and then in the Donbas. The Katehon board includes Sergey Glazyev, the economist and politician who is the current Commissioner of Macroeconomic Integration for the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU).

In 2018, Katehon pointed out that, despite all talk to the contrary, multipolarity had largely been defined as opposition to unipolarity. That is, expressed in terms of what it isn’t rather than what it is. Katehon sought to rectify this, offering its Theory of the Multipolar World (TWM):

Multipolarity does not coincide with the national model of world organization according to the logic of the Westphalian system. [. . .] This Westphalian model assumes full legal equality between all sovereign states. In this model, there are as many poles of foreign policy decisions in the world as there are sovereign states [. . .] and all of international law is based on it. In practice, of course, there is inequality and hierarchical subordination between various sovereign states. [. . .] The multipolar world differs from the classical Westphalian system by the fact that it does not recognize the separate nation-state, legally and formally sovereign, to have the status of a full-fledged pole. This means that the number of poles in a multipolar world should be substantially less than the number of recognized (and therefore, unrecognised) nation-states. Multipolarity is not a system of international relations that insists upon the legal equality of nation-states[.]

The unipolar world doesn’t protect the nation-state any more than the multipolar model does, Katehon observed. According to Katehon, the Westphalian model, in its application, has always been a myth. We might say it is just another “idea” political leaders peddle to delude us into accepting the policy goals they create. They occasionally exploit “nationalism” because it is useful.

Eurasianism

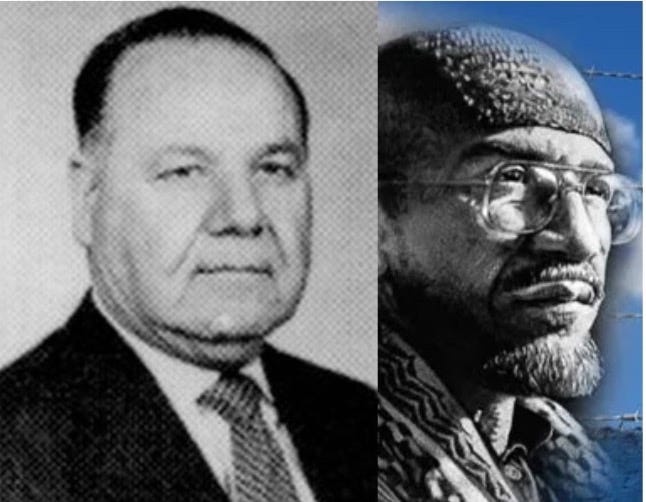

In their efforts to cast Vladimir Putin as a comic book villain, the Western mainstream media (MSM) has attempted to personally link him to the controversial Russian political-philosopher and strategist Aleksandre Dugin. They have labelled Dugin Putin’s Rasputin or Putin’s “brain” and have alleged that Putin considers Dugin a close ally and his favourite philosopher.

There was never any foundation to these stories, however. Speaking in 2018, Dugin said

“I do not hold an official position within the state apparatus. I don’t have a direct line with Putin, I’ve never even met him.”

In 2022, the Western MSM’s allegations prompted Alain de Benoist, Dugin’s political and philosophical collaborator and friend of more than 30 years, to observe:

Putin’s “brain!” The fact that Dugin and Putin have never met once face-to-face is a good measure of the seriousness of those who use this expression. [. . .] Dugin undoubtedly knows Putin’s entourage well, but he was never one of his intimates or his “special advisers.” [. . .] The book he wrote a few years ago on Putin is far from being an exercise in admiration: Dugin on the contrary explains both what he approves of in Putin and what he dislikes.

Although Dugin has no special relationship with the Kremlin, this doesn’t mean his ideas aren’t influential there. He has acted as an advisor to the Chairman of the State Duma, Sergey Naryshkin, and to the Chairman of the State Duma, Gennadiy Seleznyov, so he certainly has political connections and is heard by the Russian political class.

Dugin is perhaps the leading modern voice for Eurasianism. In a 2014 interview, he explained his interpretation of both Eurasianism and its place within multipolarity this way:

Eurasianism is based on the multipolar vision and on the rejection of the unipolar vision of the continuation of American hegemony. The pole of this multipolarism is not the national state or the ideological bloc, but rather the great space (Grossraum) strategically united within the borders of a common civilization. The typical great space[s] [are] Europe, the unified USA, Canada and Mexico, or united Latin America, Greater China, Greater India, and in our case Eurasia.[. . .] The multipolar vision recognizes integration on the basis of a common civilization. [. . .] Putin’s foreign policy is centred on multipolarity and the Eurasian integration which is necessary to create a truly solid pole.

Neither the oligarchs nor the global political class are deluded enough to believe that they can simply commend one political philosophy or another, or one cultural ideology or another, and thereby control the behaviour and beliefs of humanity. There will always be the need for some Machiavellian skulduggery.

Putin has frequently espoused Eurasianist ideas. Conversely, Dugin is among those who have criticised Putin for his lack of a clear ideology:

He must translate his individual intuition into a doctrine intended to secure the future order. He just doesn’t have a declared ideology, and that’s becoming more and more problematic. Every Russian feels that Putin’s hyper-individual approach poses a huge risk.

In 2011, Putin announced his plan to create the Eurasian Union, much to the delight of Dugin and other the Eurasianists like Malofyev and Glazyev. Putin published an accompanying article:

We suggest a powerful supranational association capable of becoming one of the poles in the modern world and serving as an efficient bridge between Europe and the dynamic Asia-Pacific region. [. . . .] It is clear today that the 2008 global crisis was structural in nature. We still witness acute reverberations of the crisis that was rooted in accumulated global imbalances. [. . .] Thus, our integration project is moving to a qualitatively new level, opening up broad prospects for economic development and creating additional competitive advantages. This consolidation of efforts will help us establish ourselves within the global economy and trade system and play a real role in decision-making, setting the rules and shaping the future.

Alexander Dugin

Putin pointed towards a global crisis that led to the claimed need for a supranational body that could act as a pole for decision-making in a global system based upon a balance of power. What he said follows a pattern; all those who extol global governance have used the same rhetorical trick.

This pattern is currently being repeated again. Irrespective of any other beliefs he may hold, Putin’s commitment to resetting the global polity is clear.

Eurasianism renders the Russian Federation a “partner” within a wider union. Currently the Eurasian Union only exists in the economic sense, and Russia is overwhelmingly dominant within it. Similarly, Russia’s permanent position in the UN Security Council affords Russia relative dominance within the UN.

Nonetheless, while the Russian government may hope to benefit from such unions and councils, by forming “poles” in a multipolar system and setting policies influenced by ideas like Eurasianism, it has diluted and declared a plan to eventually cede Russian “national sovereignty” to the union—to the pole. Putin’s pursuit of Eurasianism and multipolarity doesn’t necessarily indicate anything other than pragmatism. Nor does it represent a defence of the Russian nation-state.

We can only guess, but Putin’s preference for Eurasianism and multipolarity is unlikely to be rooted in any particular ideology. Rather, it serves a purpose, providing his government and its partners a bigger stake in “the game.”

Tianxia

Putin’s notion of “Eurasian integration” jibes with the Chinese ideology of “tianxia,” which can be translated as “everything under heaven.” In Chinese antiquity, tianxia placed the empire at the pinnacle of a global moral hierarchy. Confucian universal care dictates that a civilised state cares for its own, first and foremost, but cannot consider itself civilised if it doesn’t care for others, too.

Other states are considered civilised if they care for their citizens and barbaric if they don’t. Therefore, all civilised states should care more for the interests of other peaceful and civilised states than they do for the needs or desires of barbaric states. Consequently, bonds are naturally formed between caring states, creating a kind of organic geopolitical order, as each state places its own people at the centre of a network of civilised relationships.

In tianxia, the practice of Confucian universal care also operates within all institutions that comprise a state. For instance, civilised individuals naturally care for their families and their immediate communities more than they care for people outside those circles. However, no one is to act selfishly at the expense of other citizens, no matter where they reside, without falling into barbarism themselves.

This is a model of state that is not based upon ethnic or “blood” ties or even national borders, but rather upon a hierarchical system of morality.

Tianxia has been promoted by a few Western commentators as a “beautiful” idea. Like a philosophical Mandelbrot set it suggests a perfect moral symmetry at both at the micro and the macro scale. The multipolar world order, supposedly with tianxia at its heart, is therefore recommended as a wonderful new model of global governance and is frequently described as “win, win cooperation.”

Academics like Professors Zhao Tingyang and Xiang Lanxin have said that the global adoption of tianxia would establish a “post-Westphalian world.” This view stems from their assessment that the Westphalian order is ideologically stagnant, limited to nothing more than an expedient balance of power system wherein “might is right.”

The criticism from these tianxian scholars is not a fair reflection of the moral precepts expressed by the Peace of Westphalia—treaties that extolled the Christian values of forgiveness, tolerance and peaceful cooperation. The scholars’ assessment is, however, a reasonable appraisal of the actual conduct of Western states that only pretend to honour Westphalian principles.

Professor Lanxin points out that China “has no ontological tradition.” That is, philosophically tianxia doesn’t ask “what is this?” but rather “what path does this suggest?” If tianxia were applied to China’s strategic foreign policy, it would be ambivalent to ideas like national sovereignty.

Much like the moral foundations of Westphalian international relations, tianxia is professed but not practised. Currently, for example, China is arming the UAE and the Saudi regimes to wage war in Yemen and is also stealing Yemen’s natural resources. Is this tianxia? Where is the “win” for the Yemeni people in China’s behaviour?

The drawback of noble ideas is that they can be exploited by hard-nosed geostrategists to sell any policy agenda they like. The theories of tianxia and Eurasianism provide a grounding for multipolarity. The philosophy isn’t the problem, it is its exploitation by the engineers of multipolar global governance.

They don’t care what the intent of an idea is. They care only how they can use that ideology or philosophy to justify their actions if anyone asks. If philosophical thought suggests some useful strategies, all the better.

When global governance over a multipolar system is the goal, then tianxia, like Eurasianism, certainly is “beautiful.”

Consider the words of Professor Zhou:

[Some are] concerned that tianxia would lead to “Pax Sinica” replacing “Pax Americana.” However, this concern is misplaced because under tianxia, there would be no place for a king — the system itself is king. In this sense, it would be a bit like Switzerland, where various language groups (French, German, Italian, Romansh) and local cantons all coexist in a commonwealth of roughly equal parts where the center in Bern is essentially a coordination point with a rotating president whose power is so constrained that some Swiss citizens can’t even name the person occupying the post.

Tianxia relegates the political voice of the people to an irrelevance. It is multipolar, defining political power as a networked system that is not limited by national sovereignty or unipolar authority but rather operates “constrained” centres of power. For those who manipulate geopolitics covertly, it is perfect: the system itself is king.

Tianxia may be a serene philosophy, but what really matters is how the theory is applied to policy. The 2017 authorised publication titled Forge Ahead under the Guidance of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s Thought on Diplomacy by China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi gives us a glimpse of the kind of thing China’s political class and others call “win, win cooperation.”

Xi Jinping […] puts forward new propositions on security, development and global governance. […] Xi Jinping […] has underscored China’s role and contribution to world peace and development and to upholding the international order. […] China has […] played a leading role in the Asia-Pacific cooperation, the G20’s transformation and the course of economic globalization[.]

[…] China has promoted the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the Silk Road Fund and the BRICS New Development Bank, and has taken an active part in the formulation of rules governing such emerging areas as marine and polar affairs, cyberspace, nuclear security and climate change.

[…] The [Belt and Road] initiative has been widely commended for lending impetus to global growth and boosting confidence in economic globalization.

[…] We have taken an active part […] and worked with other countries to tackle global challenges such as terrorism, climate change, cyber security and refugees. […] We advocated the formulation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and became the first country to release its national plan on implementation.

It turns out that the alleged application of tianxia means upholding the international order, international financial and monetary system reform, Agenda 2030, counterterrorism, controlling human capital, exercising global cybersecurity, economic globalization and, of course, global governance.

It seems Xi Jinping’s tianxia-inspired “thoughts” are just the same as the thoughts of the Rockefellers, Vladimir Putin, Klaus Schwab and all other members of the multipolar sales team.

Russia – The Fusion of the Public-Private Oligarchy

The Russian government and its think tanks and and oligarchs are not alone in advocating a “regionalized” world of poles. With its five “groups,” a nascent multipolar world order already exists in the form of the G20. The G20’s enthusiasm for a single global tax system demonstrates the intention to move toward a much firmer system of global governance.

Previously we noted that Putin purged the oligarch collaborators of the West in fairly short succession after becoming President. Much has been written about his war against the “5th columnists.” This often infers that Putin is somehow opposed to the power of oligarchs. That isn’t true at all.

The Russian government has no problem with people making huge amounts of money and then using it to exercise political power. It is just that political power must promote the Russian government’s aspirations.

In fact, one of the perks of being in Putin’s circle is the opportunity to become fabulously wealthy. We have already discussed the obscene levels of wealth inequality in Russia, particularly in terms of its concentration in the hands of the oligarchs. Putin hasn’t put an end to this elitism; he has facilitated it on a grand scale.

To put the matter in perspective: when Putin became President in 1999—that is, “elected” in 2000—there were a handful of Russian billionaires and oligarchs. Today, according to Forbes, there are more than 100.

Perhaps it is just another coincidence, but the sanctions have provided an impetus for Russian oligarchs living overseas to return to the motherland, a trend that has effectively strengthened the Kremlin’s bond with its oligarch “partners.”

In 1999, Putin inherited a Russian economy that had been holed out. Between 1999 and 2014, he oversaw a remarkable Russian economic recovery. Living standards improved significantly, GDP rose from $200 billion in 1999 to $2.2 trillion in 2014.

Putin led Russia from the 20th largest economy in the world to the 7th (now 11th). It seems that luck—or price fixing!—may have played a part in this apparent economic miracle. Russia’s GDP growth tracks the global oil price quite precisely.

While the Russian people benefited from some of this growth, fuelling a consumer boom, the same period also saw a huge increase in wealth inequality. A new class of Russian oligarchs hoovered up a disproportionate share of Russia’s national wealth. During his 2000 campaign to be formally anointed as President, when a radio journalist asked Putin how he would define “oligarch” and what he thought of them, he said:

[The] fusion of power and capital — there will be no oligarchs of this kind as a class.

Once secured in power, though, Putin’s team constructed a crony capitalist regime that is the epitome of the “fusion of power and capital.” He and his entourage effectively inverted the Western model of oligarch control, where capital is converted into political power. In Russia, political power enables the accumulation of capital, creating an almost unique class of oligarchs.

Gazprom, the world’s largest publicly listed gas company, provides a case study demonstrating how the Russian oligarchy functions.

Dmitry Medvedev and Alexei Miller worked in St Petersburg alongside Putin during the 1990s. Medvedev was the mayoral campaign manager for Anatoly Sobchak, who subsequently co-authored the Constitution of the Russian Federation. Putin was an advisor and then deputy to Sobchak. Miller served on the mayor’s Committee for External Relations.

When Putin became President, he gave Medvedev the highest civil service rank in Russia and made Miller the Deputy Minister of Energy.

Meanwhile, Putin decreed that Gazprom was a “national champion”—meaning a “private” corporation the Russian government considers essential to the Russian economy. Through various funds, the Russian government retained its 50.2% controlling interest in Gazprom, which makes Gazprom a public-private partnership.

Putin appointed Medvedev and Miller to the Gazprom board. Medvedev acted as chairman until 2008, when he was selected as the nominal President of the Russian Federation, while Putin temporarily acted as Prime Minister for a few years. Miller was appointed as Gazprom CEO in 2001 and is still in that post.

In 2006, Gazprom released the construction cost of its Altay pipeline from West Siberia to China. The same year it also released the expenditure figures for its Gryazovets-Vyborg pipeline. The per-kilometer cost of the Gryazovets-Vyborg pipeline was four times higher than the comparable Altay pipeline or similar pipelines, such as the OPAL pipeline in Germany.

In 2008, the Russian firm PiterGaz Engineering estimated the total construction cost of the Sochi pipeline to be $155 million—at the current exchange rate. Yet Gazprom paid the present-day equivalent of $395 million.

This inflated price prompted the East European Gas Analysis (EEGA) to note:

Russian pipeline engineering institutions, including the corresponding divisions of Gazprom, give realistic estimations of pipeline construction costs, comparable with those of western projects. However, it looks like, on the way to the top management of Gazprom, these cost estimations get at least tripled. [. . .] Apparently, after getting a realistic cost estimation, Gazprom executives add a generous margin for contractors and brokers, so the total project cost gets 3-4 times higher.

Such slush funds are found in every sector of the Russian economy, most notably in defence, infrastructure development and healthcare. The proceeds are then doled out to loyal oligarchs.

They are “oligarchs” in the fullest sense of the word. Their wealth is dependent upon their partnership with the political state. In return, they use their wealth to forward the policies of the state. Their capital couldn’t be more “political.”

For example, Alexey Mordachov owns the steel giant Servestal that supplies gas pipeline to Gazprom for its development projects, such as the Yakutia-Khabarovsk-Vladivostok pipeline (aka the China–Russia East-Route).

Other oligarchs profiting from the scheme include Putin’s personal friends Gennady Timchenko, who owns the OAO Stroytransgaz construction company, and Arkady Rotenberg, whose Stroygazmontazh (S.G.M. Group) forms Russia’s largest gas pipeline and power grid construction company.

The oligarchs are profiting from the construction of the Arctic Silk Road.

They deploy their resources to ensure that the Russian government’s foreign policy objectives are realised. The Russian oligarchs and the Russian political class are in a symbiotic relationship: a public-private partnership constructing the multipolar world order.

In so doing, they are engaging in the Great Reset, implementing the Rockefellers’ vision and fulfilling the dreams of Carroll Quigley’s Anglo-American network. The Russian state is more than just a public-private partnership. Moving beyond mere contractual arrangements and shared strategic goals, Russia’s government has fused the corporate and the political into a single public-private nation-state.

Despite the slaughter going on in the Ukraine war and all sides’ refusal to unconditionally negotiate, Russia’s “state-owned” private energy corporation Gazprom has apparently settled its dispute with Ukrainian “state-owned” energy corporation Naftogaz and is pumping 42.4 million cubic meters of natural gas a day through Ukraine to Western Europe energy markets.

The Russian Federation is paying the Ukrainian government substantial transit fees. It is effectively funding Ukraine’s war effort. The war is only for the little people.

China – The Fusion of the Public-Private Oligarchy

The only major developed economy in the world to have gone further than Russia in fusing the public and private sectors is China. China is a neo-fuedal capitalist state operating as a technocracy under the leadership of an oligarch dynasty.

The great military and political leaders of Mao Zedong’s revolution who later successfully evaded Mao’s Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) were collectively referred to as the “eight immortals.”

When the Rockefellers and the Trilateral Commission dispatched Henry Kissinger to prepare the ground for US President Nixon’s visit to China in the early 1970s, seven of the immortals decided to throw their collective political weight behind fellow immortal Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms.

Deng Xiaoping

The process of opening up China’s economy began in earnest following Mao’s death in 1976. Prominent Trilateralists such as then-US President Bill Clinton, global investment firms, Western-based multinational corporations and private investors stepped up foreign direct investment to assist China’s immortals in modernising the country’s economy, financial sector, military, industrial and technological capability. The modernisation enabled the rise of China’s oligarchy.

For example, the immortal General Wang Zhen supported Deng’s economic liberalism but also sliced off huge chunks of China’s state assets and placed them in trust to his son, Wang Jun.

Subsequently, Wang Jun collaborated with Deng’s economic advisor, Rong Yiren, to seed his now private capital into Citic Group Corp, which then became China’s “state-owned” investment company.

Citic Group is a public-private partnership that today has significant influence over China’s financial services, advanced manufacturing technology, production of modern materials and urban development.

In this way the immortals effectively created a public-private dynasty in China. Their immensely wealthy offspring are now collectively referred to as the “Princelings.”

The Princelings can broadly be divided into three groups, each influencing important Chinese sectors and industry:

- political Princelings, such as Xi Jinping, manage the public sector

- military Princelings manage the defence and national security sectors

- entrepreneur Princelings manage the private sector.

As a group, they have huge influence over China’s domestic and foreign policy.

China is a one-party state but has not abandoned politics. The selection of Xi Jinping as Paramount Leader in 2012 marked an effective power-shift toward the Princelings, who many consider to represent the “elite.”

They are “opposed” by the “Tuanpai,” whose power base stems from the Communist Youth League movement established by former president Hu Jintao. The Tuanpai are broadly popularist and more focused on the issues of working Chinese people.

Other factions, such as the “Shangai Gang” and the “Tsinghua Clique,” add to the political mix.

Technocracy controls citizens through the allocation of resources. China leads on the technocratic aspects of the Great Reset. It is the world’s first operational Technate, wherein the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) oversees the surveillance and control of the population through its social credit system:

The establishment of a social credit system is an important foundation for comprehensively implementing the scientific viewpoint of development. [. . .] Accelerating and advancing the establishment of the social credit system is an important precondition for promoting the optimized allocation of resources.

The idea is that citizens can be rewarded for good behaviour and penalised for bad. Speaking to French Television, one of the lead developers of China’s social credit system was asked how French adoption of it might have impacted the Yellow Vest protests in France. Lin Jinyue replied:

I really hope that we will manage to export it in a capitalist country. [. . .] I believe that France should quickly adopt our system of social credit, to regulate their social movements. [. . .] If you had had the system of social credit, the Yellow Vests would never have been.

Coincidentally, social credit-style surveillance has been greatly enhanced as a result of the pseudopandemic that began in China. To travel on public transport, enter civic buildings, be admitted to the workplace and so on, it is necessary for China’s citizens to scan their COVID Pass QR code. Green allows them to move freely; Red prevents their free movement.

Biometric identification via facial recognition scanning is required to register a sim card in China. The biometric data system allows the NDRC to track the movements of every citizen and allows biosecurity to be enforced nationally.

Covid QR codes, combined with digital ID, means that China’s Technate is on its way to meeting the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 3 and 16.

SDG 3 reads:

Strengthen the capacity of all countries, in particular developing countries, for early warning, risk reduction and management of national and global health risks

And SDG 16 says:

By 2030, provide legal identity for all, including birth registration

“Legal identity” is UN code for digital identity.

The Chinese technocratic oligarchy is also ahead of other countries in its development and implementation of Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC). Bo li recently vacated his position as the Deputy Governor of the Bank of China to join the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as its Deputy Managing Director.

Speaking at the IMF’s Central Bank Digital Currencies for Financial Inclusion: Risks and Rewards symposium, Bo Li discussed the claim that CBDC would improve so-called “financial inclusion”:

CBDC can allow government agencies and private sector players to program [CBDC] to create smart-contracts, to allow targetted policy functions. For example[,] welfare payments [. . .], consumptions coupons, [. . .] food stamps. By programming, CBDC money can be precisely targeted [to] what kind of [things] people can own, and what kind of use [for which] this money can be utilised. For example[,] for food. So this potential programmability can help government agencies precisely target their support to those people who need support. So, in that way we can also improve financial inclusion.

Perhaps so—although the improvement will only be afforded tothe citizen who obeys the”government agencies and private sector players”—the Princelings. Engage in “bad” behaviour and and CBDC will be used to target you for financial “exclusion.”

With CBDC in place, there would be no need to switch people’s QR code to red to stop them from attending a protest. Simply program their CBDC to prevent train ticket purchases or the use of money more than a mile from home. Physical lockdowns of Covid days are replaced by CBDC lockouts, which are much easier to enforce.

Bo Li speaking at the IMF symposium

The Multipolar Military Dimension

Global economic and financial power is backed up by military force. So if the powers-that-be are serious about building a new system of super-powered poles, they need to have the muscle to hold their respective positions. After all, a multipolar world order cannot be stabilised and enforced unless each pole presents a genuine military threat to the other.

For most of the post-WWII period, the US-led unipolar NATO alliance possessed the most advanced military technology. Not only did the West dominate monetarily, financially and economically, it had the military advantage to go with it. Yet, just like every other aspect of former Western dominance, that, too, has disappeared, and military power has blossomed elsewhere.

Suddenly, as if from nowhere, Russia is claiming technological military supremacy. It is now ahead in the arms race. The US has confirmed that Russia used a functioning hypersonic missile in Ukraine, a fact that Joe Biden called “consequential” and frankly admitted “is almost impossible to stop.”

China, too, has fired a hypersonic missile. It apparently circled the globe. It then dispatched a hypersonic glide missile that struck its target in China. Again, confirmation came from senior US military officials, who called the technological advance “stunning.”

Now China says it may soon be able to arm its navy with these superior weapons.

Meanwhile, the West’s dunderheads, who until relatively recently dominated militarily, simply can’t wrap their minds around the ramjet engine technology (or scramjet) that powers this new breed of missiles.

While China has confirmed global flight tests and pinpoint hypersonic accuracy and Russia has actually used them in the battlefield, the Pentagon and the US Defence Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA) and its private-sector partners like Raytheon are still fumbling about with limited tests, hoping they might be able to develop the same operational capability sometime soon.

If you can believe that!

The British can’t build ships that function in warm water, and their aircraft carriers can’t sail more than a few nautical miles without breaking down.

The US Navy can’t sail its ships at all.

And no one in the West can build a fighter aircraft that actually works. Yet Russia has taken submarine technology to a new level, and everyone is pretty sure China has developed AI “intelligentized” fighting capability.

The West’s sudden inability to stay in, let alone lead, the technological arms race certainly seems to mark a polar shift in the global military balance of power. It is likely that the Western military-industrial complex is kicking itself after spending the last 30 years handing its military technology over to the East.

Now look what they’ve done!

Conclusion

The Russian government and the Chinese government are not “worse” than the US, the UK or the French government. They are just governments doing what governments do. They represent the interests of those who can keep them in power—or remove them.

The multipolar world order ends the last vestiges of national sovereignty. It is the geopolitical Great Reset: the culmination of the oligarch’s longstanding plan to establish a system of global governance that affords them dominion over all.

If the multipolar system proceeds, which seems likely, the 193 nations—give or take—of the world will eventually be incorporated into a few global poles. Who knows how many, but probably no more than half a dozen or so.

There are some potential benefits to multipolarity. Perhaps tianxia will break out, thus reducing the risk of conflict. A “balance of power” between global poles of states could limit aggression. But if we consider how this might be achieved and who is supposedly leading it, there is reason for concern.

Assuming that the Pax Americana, Pax Europa, Pax Eurasia and Pax Sinica poles, or whatever, don’t intend to disarm, wouldn’t this logically infer a proliferation of armaments globally, including hypersonic nuclear weapons? How will these poles maintain internal security? What is to stop warfare from breaking out within each pole as disputes emerge? Will other poles have to, or choose to, intervene?

Let’s be honest. The omens don’t look too encouraging. We are accelerating towards the multipolar world order due in large part to a war currently being waged by one of multipolarity’s leading proponents. Similarly, the activities of the other leading proponent—in places like Yemen, for instance—hardly inspire confidence.

There is no evidence to suggest that the conduct of either Russia or China is or will be intrinsically “better” than the conduct of the leading nations of the previous “order.”

By far the most concerning aspect of the multipolar world order is that fewer “poles” will empower global governance. The consistent trajectory, throughout history, toward the centralisation of power hasn’t just happened by accident. The strategy of diminishing the clique of people who exercise control over the global population is a purposeful one. Were it not, it wouldn’t have been engineered in the first place.

The goal of these technocrats is to possess unopposed power. We know what they desire to do with that power should they ever achieve it:

- enhanced biosecurity

- population control

- population surveillance

- digital IDs

- social credit systems

- AI automated censorship

- Universal Basic Income

- control of the food supply, of water, of energy, of housing, of education

- ultimately, the total control and enslavement of humanity through Central Bank Digital Currency, or some variation of it.

The nation-states advocating the new multipolar world order don’t reject these control mechanisms. On the contrary, they are leading in of their development. The multipolar system is one giant leap toward global technocratic tyranny, a system they fully endorse.

In Part 1, we noted that US geostrategist Zbigniew Brzezinski had identified Eurasia—”extending from Lisbon to Vladivostok”—as the setting for what he called “the game.” He observed:

America must absolutely take over Ukraine, because Ukraine is the pivot of Russian power in Europe. Once Ukraine is separated from Russia, Russia will no longer be a threat.

US-led Western powers, having orchestrated the 2014 Euromaidan Coup and having failed to seize control through the Ukrainian ballot box, have since then demonstrated their intent to incorporate Ukraine into the West’s strategic orbit by any means. Conflict of some sort became inevitable from that point onwards. The next eight years saw an escalating proxy conflict unfold, with virtually no serious attempts to stop it, which has led to this entirely predictable Ukraine War.

The people of Ukraine and the people in the new Russian republics and oblasts of Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporozhye and Kherson are viewed as expendable pawns. The conflict is all too real for them, as they fight and die and long to live in peace without the perpetual threat of violence. Yet neither the “great powers” nor their puppet leaders care about the lives of the people beyond their strategic value.

The war in Ukraine is a deadly tactical ploy. The point is to fight it out, down to the last Ukrainian, if necessary, in order to facilitate the transition to the multipolar world order, thus enabling the abhorrent Great Reset and finally delivering full-blown global governance.

The vulnerable ones who will freeze to death in Europe this winter—and they could number in the thousands—are mere collateral damage in “the game.”

Yet war needn’t get in the way of business as usual: Russia continues to supply gas to Europe, if in greatly reduced quantities and at elevated prices, through Ukrainian pipelines.

The mainstream media and much of the alternative media, in both the West and the East, market the Ukraine war as a battle for “freedom,” “sovereignty” or some such drivel. As the death toll mounts among those forced to fight for their existence, we in the wider international community, taking one side or the other, fall for the same old monstrous lies.

We plant our little flags, online and off, and argue about our respective delusions, imagining that we are participating in the war, in our own small way. We act like jeering football crowds who cheer on our side to win.

Globalist think tanks have long considered war a strategic catalyst for change, a point we should have learned from Norman Dodd’s investigation and report for the Reece Committee on Foundations in 1954. We are being hopelessly naive if we imagine the war in Ukraine couldn’t possibly lead to a horrific global conflict. We have no reason to “trust” the lunatics whom we allow to remain in charge.

Equally, we should recognise that we are being manipulated by tactics designed to produce fear. Nuclear brinkmanship should always be seen in its fear-inducing context.

The oligarchs of the world are united as they seek to establish a regionalized, multipolar system of global governance that will rule the nation-states we live in.

Our political leaders, wherever they exert their claimed authority, are wholly complicit with the oligarchs’ agenda. They are selling us all out as they vie for a better seat at the table while breaking our backs in their obsequious desire to polish it.

No comments:

Post a Comment